(2: 安徽升金湖国家级自然保护区管理局 池州 247200)

(2: Lake Shengjin National Nature Reserve of Anhui Province, Chizhou 247200, P.R.China)

动物肠道微生物群落具有丰富的种类和功能多样性[1],这些微生物之间及微生物和宿主之间存在稳定复杂的关系.许多情况下,动物及其肠道微生物之间互利共生,协同进化[2].随着16S rRNA作为微生物标记基因的应用以及高通量等分子生物学技术的发展,加之粪便取样手段的引入,肠道微生物,特别是肠道微生物对宿主生理功能的影响,已经成为近年来研究的热点问题[3].动物胃肠道菌群对宿主的营养、消化和吸收方面具有重要作用,肠道微生物含有很多分解酶可以降解食物中不易消化的成分,如多糖类纤维素类物质[4],并且可以合成氨基酸、脂肪酸及维生素等宿主必需物质[5].同时肠道微生物在宿主免疫功能上也有重要作用[6].

肠道微生物在影响宿主动物生理功能的同时,其菌群结构也受到宿主生存环境的影响[7],特别是宿主食性不仅能够影响,而且在一定程度上能够决定肠道微生物菌群组成[8].有研究表明,动物肠道微生物数目由肉食性到杂食性再到草食性呈逐步增加趋势[9].在对人的肠道微生物研究时,由于饮食习惯的不同,不同地区生活的居民的肠道微生物菌落结构具有很大的差异,而相同地区生活的居民的肠道微生物菌落结构相似性较高[10-12].肠道微生物菌群结构对于动物的食性具有很强的适应性,大熊猫(Ailuropoda melanoleuca)以竹子为主要食性,含有丰富的纤维素,在长期的进化过程中,在其肠道微生物中含有丰富的能够分解纤维素的梭菌属(Clostridium)[13].

白头鹤(Grus monacha)属于鹤形目,鹤科,为大型迁徙水鸟,属于国家Ⅰ级重点保护野生动物,世界自然保护联盟(IUCN)红色物种名录中的易危物种[14],长江中下游的升金湖是白头鹤的重要越冬地,每年在此越冬的白头鹤大约在300只左右[15].升金湖作为浅水内陆湖泊,含有丰富的生物资源,特别是每年冬季,大量的滩涂暴露,为越冬水鸟提供丰富的食物资源以及觅食栖息地[16].近几年,由于湖泊渔业养殖、围垦造田、水利建设、旅游开发等人为因素的干扰,白头鹤的栖息地不断退化,适宜的觅食生境不断丧失[17].升金湖越冬白头鹤觅食的主要生境为稻田和草滩[18],但在不同的越冬阶段,它们的相对重要性发生变化[19].白头鹤在越冬前期选择稻田作为主要觅食生境,以稻谷作为主要食物;越冬中期,白头鹤对稻谷的利用率相对前期降低,但仍以稻谷作为最主要的食物资源;越冬后期,白头鹤逐渐选择草滩生境作为其主要觅食生境,以朝天委陵菜(Polygonum criopolitanu)作为主要食物资源[20].因此,不同越冬阶段白头鹤肠道微生物菌群组成的研究对于了解食物资源变化对肠道微生物菌群结构的影响具有重要意义.

本文通过16S rRNA高通量测序技术,研究升金湖越冬白头鹤不同时期肠道菌群组成情况,揭示越冬不同时期白头鹤肠道菌群组成的差异,结合食物资源的变化,探讨越冬白头鹤肠道微生物与外界环境之间的关系,为白头鹤越冬生理生态和种群管理提供基础资料.

1 材料和方法 1.1 样品的采集与保存根据白头鹤的迁徙规律和越冬地的自然气候特征,将白头鹤越冬期划分为3个时期,即越冬前期、中期和后期[21].于2014年12月—2015年4月,采用非损伤采样技术采集安徽省升金湖(30.25°~30.50°N, 116.92°~117.25°E)越冬白头鹤的粪便样品.按照3个越冬时期采样, 即:2014年11月上旬—2014年12月下旬,越冬前期;2015年1月上旬—2015年2月下旬,越冬中期;2015年3月上旬2015年4月上旬,越冬后期.前期和中期采样时间间隔为34天,中期和后期的采样时间间隔为55天(表 1).

| 表 1 3个越冬时期白头鹤粪便样采集的详细信息 |

在采集粪便样品前,用双筒望远镜和单筒望远镜观察白头鹤集中觅食区域,选择集群较大的群体,观察确保在白头鹤觅食期间周围50 m范围内没有其他鹤以及雁鸭类存在或者活动.等到白头鹤取食结束离开觅食地后,立刻前往觅食地点进行采集,根据白头鹤留下的足迹或觅食坑,确定为白头鹤觅食地点.戴一次性消毒手套并用镊子采集白头鹤新鲜粪便样品,去除接触地面的部分后,迅速将样品放入无菌50 ml离心管中,并贴好标签,放在冰上运回实验室,置于-80℃超低温冰箱冷冻保存(表 1).

1.2 DNA的提取本实验采用德国QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit粪便微生物基因组DNA提取试剂盒来提取粪便样品中的细菌基因组DNA,提取方法严格按照试剂盒制造商的具体操作步骤进行,DNA提取样品保存在-20℃超低温冰箱中以备后续实验使用.

1.3 16S rRNA基因扩增及高通量测序选择通用引物338F (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′)和806R(5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′)作为这次实验的扩增引物[22],对细菌16S rRNA V3~V4区进行PCR扩增.实验采用20 μl反应体系:10×ex Buffer,2 μl;0.25 mmol/L dNTPs,2 μl;正反向引物(20 mmol/L)各0.5 μl;DNA模板,10 ng;exTaq DNA Polymerase, 0.5 μl; ddH2O,12.9 μl. PCR反应循环程序设置:94℃预变性3 min;95℃变性30 s;55℃退火30 s;72℃延伸45 s,反应27个循环后72℃终端延伸10 min,终止于4℃. PCR产物经2 %琼脂糖凝胶电泳鉴定.将符合标准的样本送至上海美吉生物医药科技有限公司,利用Illumina Miseq测序平台进行高通量测序.

1.4 数据分析高通量得到的原始数据都是以Fastq文件格式保存,首先对原始测序数据进行质量控制(去除含有模糊碱基、含有6个以上单碱基高重复区、长度小于200 bp的序列),获得纯净序列;通过COPE(Connecting Overlapped Pair-Eend, V1.2.1)软件对序列进行拼接,并去除上、下游引物,最终得到优化数据.运用USEARCH(Vsesion 7.1http://drive5.com/uparse/)按照97 %相似性对非重复序列(不含单序列)进行OTU(Operational Taxonomic Units)归类操作并进行OTU丰度统计,运用Mothur进行Rarefaction分析,利用R语言工具绘制稀释性曲线图(Rarefaction Curve)[23].采用RDP Classifier贝叶斯算法对97 %相似水平的OTU代表序列进行分类学分析,并在各个分类水平统计每个样品的群落组成,置信度阈值为0.7[24].应用Mothur分析软件,在97 % OTU水平上计算Alpha多样性指数(包括物种丰富度的两个指数(Chao1和Ace))、辛普森(Simpson)指数和香农威纳(Shannon-Wiener)指数[25].运用R语言软件绘制主坐标分析图(Principal Co-ordinates Analysis,PCoA),研究样本群落组成的相似性.应用SPSS 19.0软件对样品数据进行统计学分析,P < 0.05时为具有显著性差异.

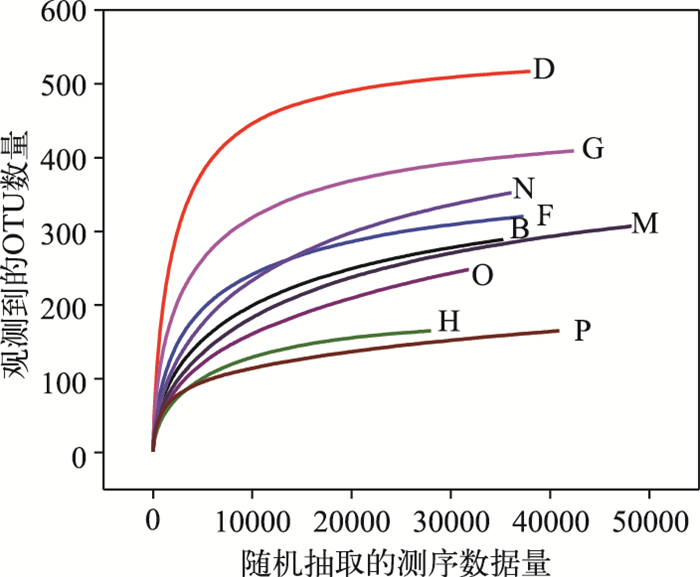

2 结果与分析 2.1 细菌的Alpha多样性9个样本共得到337447条有效序列,平均每个样品测得37494条有效序列(表 2).序列长度在428~ 447 bp之间,符合16S rRNA基因V3~V4区域及引物设计长度.序列经过聚类后共得到708个OTU.采用对序列进行随机抽样的方法,以抽到的序列数与它们所能代表OTU的数目构建稀释性曲线(图 1),用来说明样本的测序数据量是否合理. 图 1结果显示,在测序量比较小时,随着测序量的增加OTU数量会显著增加,而随着测序量的逐渐增大新增OTU的数量逐渐变少,曲线趋于平坦,说明本研究中的测序数据量合理,更多的数据量只会产生少量新的OTU.通过方差分析对3个时期OTU数量进行统计分析,得到F2, 6=0.034,P=0.967,表明基于本文的数据,3个时期OTU数量未检测出显著性差异.而通过取3个时期OTU数量平均值,越冬前期为323个,越冬中期和越冬后期分别为298和302个,说明在越冬前期粪便中的微生物丰度最高. 表 2为越冬前中后期白头鹤肠道微生物的Alpha多样性指标,覆盖率都在99 %以上,为进一步了解升金湖越冬前中后期白头鹤肠道菌群丰度和多样性变化,通过方差分析对各个Alpha多样性指标进行统计分析,得到Ace (F2, 6=0.434,P=0.667)、Chao1 (F2, 6=0.243,P=0.792)、香农威纳指数(F2, 6= 0.095,P=0.911)和辛普森指数(F2, 6=0.229,P=0.802),表明基于本文的数据,并未检测出显著性差异.

|

图 1 稀释性曲线(大写字母代表样品编号,下同) Fig.1 Rarefaction curve |

| 表 2 3个越冬时期白头鹤肠道菌群的多样性及丰富度指数 Tab.2 Diversity and richness of gut microbiota in Hooded Cranes in the three wintering periods |

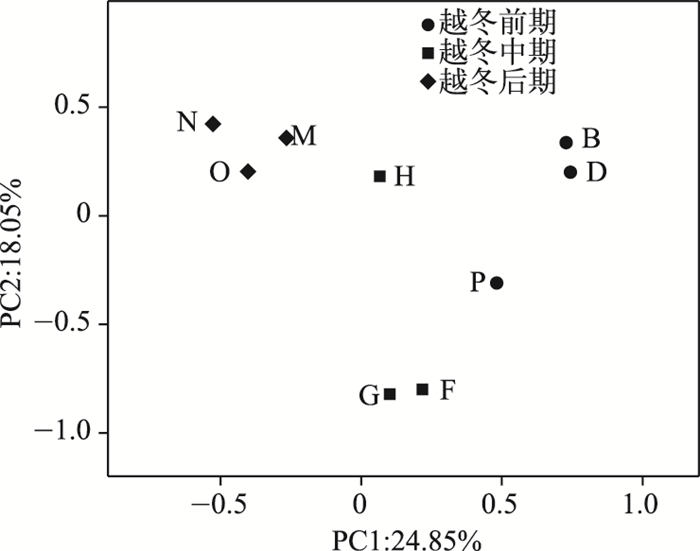

本文运用主坐标分析形象化地展示3个时期粪便微生物组成的差异性.结果表明,同一个越冬阶段的粪便样品微生物菌群组成相似性较高,而不同越冬阶段的粪便样品微生物菌群组成差异性较高(图 2).

|

图 2 主坐标聚类分析 Fig.2 Principal co-ordinates analysis |

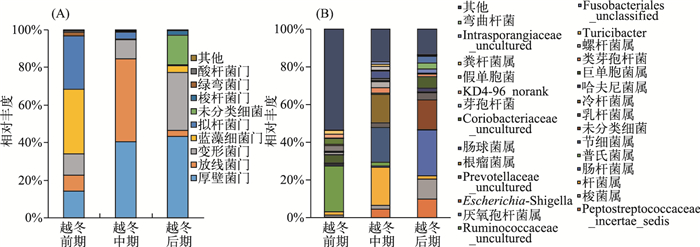

9个升金湖白头鹤粪便样品共检测出26个门.越冬前期共鉴定到20个门,优势菌门为厚壁菌门(Firmicutes, 14.2 %)、蓝藻细菌门(Cyanobacteria, 34.5 %)、拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes, 28.2 %);越冬中期共鉴定到15个门,优势菌门包括厚壁菌门(40.4 %)、放线菌门(Actinobacteria, 44.2 %)和变形菌门(Proteobacteria, 10 %);越冬后期共鉴定到18个门,优势菌门包括厚壁菌门(43.2 %)和变形菌门(31 %).

在3个时期都检测出的门有12个,其中厚壁菌门、变形菌门、放线菌门、拟杆菌门和蓝藻细菌门存在于所有样品中,并且作为优势菌,在总序列中的比例达到92.3 %.越冬前期厚壁菌门较中后期含量较低,而拟杆菌门(28.2 %)相对越冬中期(3.6 %)和越冬后期(0.4 %)含量较高;越冬中期放线菌门(44.2 %)较越冬前期(8.4 %)和越冬后期(3.2 %)含量高;越冬后期变形菌门含量(31 %)较越冬前期(11.2 %)和越冬中期(10 %)高,并且越冬后期未能鉴定的门含量较高,明显高于越冬前期(0.05 %)和越冬中期(0.1 %),表明越冬后期样品中存在大量未知的新类群(图 3A).

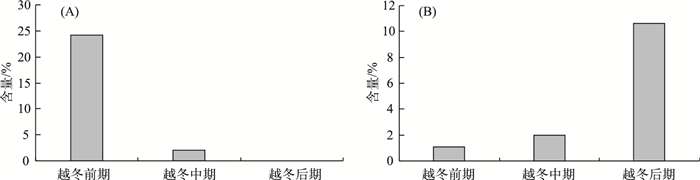

2.3.2 属分类水平分析9个升金湖越冬白头鹤粪便样品共检测到252个属,主要属在9个样品中的分布见表 3.从图 3B可以看出3个时期粪便样品菌群在属水平上的分布,越冬前期共鉴定到201个属,优势菌群为普氏菌属,平均比例为24.3 %,要明显高于越冬中期(2.1 %)和越冬后期(0.01 %).并且其含量从越冬前期到越冬中期再到越冬后期有明显的降低趋势(图 4A),在越冬后期的3个样品中只存在于样品N中.越冬中期共鉴定到175个属,优势菌为杆菌属(20.3 %)、节细菌属(18.3 %)和冷细菌属(15 %).越冬后期共鉴定到182个属,占优势的菌群为肠杆菌属(24.4 %)和梭菌属(10.6 %),其中梭菌属含量要显著高于越冬前期(P=0.046),明显高于越冬中期(2 %),并且从越冬前期到越冬中期再到越冬后期有明显的升高趋势(图 4B).另外细菌纤维菌属(Cellulomonas)和Cellulosilyticum在白头鹤肠道微生物中的平均含量也呈现出越冬后期(0.1 %、0.4 %)明显大于越冬前期(0.02 %、0.05 %),这两种细菌也可以降解食物中的纤维素.

| 表 3 升金湖越冬白头鹤粪便微生物属分类水平的分布 Tab.3 Genus-level distribution of the faecal microbiota from the overwintering Hooded Cranes at Lake Shengjin |

|

图 3 3个越冬时期白头鹤肠道菌群的门(A)和属(B)组成 Fig.3 Gut microbiota composition in Hooded Cranes at the phylum (A) and genus (B) taxonomical levels in the three wintering periods |

|

图 4 普氏菌属(A)和梭菌属(B)在越冬前、中、后期的含量 Fig.4 Contents of Prevotella (A) and Clostridium (B) in the three wintering periods |

3个时期升金湖越冬白头鹤肠道微生物菌群结构特征均表现出含有较高的肠道微生物多样性,越冬前、中、后期肠道菌群OTU数量以及多样性指数并没有显著性差异.但越冬前期OTU数量平均值最高,并且检测到的门和属最多,说明在越冬前期检测到的细菌丰度及细菌种类最多.通过主坐标分析,越冬前、后期样品分别表现出相似性,表明越冬前、中、后期白头鹤肠道菌群组成可能存在差异性.动物的生存环境,特别是食性变化影响其肠道微生物菌群结构[26],以前的研究显示越冬期间白头鹤觅食栖息地会发生变化,升金湖越冬白头鹤在越冬前期主要以稻田生境为觅食栖息地,越冬后期主要以草滩生境为觅食栖息地[18],这两个时期食物相对单一,可能造成白头鹤肠道菌群组成分别在这两个时期表现出一定的相似性,而越冬中期作为两个时期的过渡期,生境异质性较大,食物多样化,可能造成白头鹤肠道菌群构成在越冬中期相对于越冬前期和越冬后期差异性大.

升金湖白头鹤肠道微生物在门分类水平上主要由厚壁菌门、变形菌门、放线菌门、拟杆菌门和蓝藻细菌门组成,与猪、马、牛等哺乳动物以及麝雉、火鸡、家禽等鸟类相似[27-30].属分类水平上,共检测到252个属,以普氏菌属、肠杆菌属、杆菌属、节细菌属、梭菌属和冷杆菌属最为常见,这与猪的肠道微生物在属水平上以放线杆菌属、嗜血杆菌属、巴氏杆菌属、消化链球菌属、梭杆菌属、韦永氏球菌属为主有差异,而与以草为主要食性的马在肠道微生物分布上相似性较高,都含有较高的普氏菌属和梭菌属,并且都含有纤维菌属.

不同越冬阶段下白头鹤肠道菌群组成分析表明,在越冬前期,拟杆菌门作为其优势菌,其中普氏菌属比例较高,有关研究表明这种菌群结构在人类和其他动物的肠道微生物菌群结构中普遍出现[31-32].这种菌群结构的普遍存在可能与其功能有关,根据以前的研究,拟杆菌门主要参与碳水化合物发酵以及多糖、胆汁酸和类固醇代谢[33],而普氏菌属作为拟杆菌门中的重要细菌,主要参与肠道中碳水化合物以及植物蛋白质的分解代谢[34],稻谷中含有大量的植物蛋白质、淀粉和脂肪,并且在以谷物等食性为主的人群的肠道菌群中含量较高[35-38]. 3个时期越冬白头鹤肠道菌群组成分析表明,普氏菌属作为越冬前期的优势菌,高于越冬中期和后期,并且随着越冬时间呈现降低趋势;而具有降解肠道中纤维素作用的梭菌属[13],在越冬后期含量较高,显著高于越冬前期,明显高于越冬中期.这可能与升金湖越冬白头鹤在越冬期间觅食栖息地及食性变化有关:越冬前期白头鹤以稻谷为主要食性,越冬中期对稻谷利用率降低,在越冬后期稻田生境受到长时间的觅食消耗和春耕等原因,食物利用率最低[17];而随着越冬时间的推移,在越冬后期,进入早春阶段,植被快速生长并进入花期,白头鹤逐渐把草滩作为主要觅食地[39],食物中可能含有较高的纤维素.通过对2011年11月—2012年4月升金湖越冬白头鹤粪便进行显微镜观察,不同越冬期白头鹤食物组成不同:前期为稻谷、蓼子草(51.96 %、16.20 %);中期为稻谷、朝天委陵菜(30.94 %、17.16 %);后期以朝天委陵菜、稻谷(46.74 %、14.31 %).其中稻谷、蓼子草随着越冬期的变化相对密度逐渐减小,朝天委陵菜逐渐增大[21].这一结果表明,白头鹤越冬不同阶段食物资源的变化可能对其肠道菌群组成造成了一定的影响,这种影响机制后期还需要进一步深入研究.

4 结论本文对不同越冬阶段下的白头鹤肠道菌群组成做了初步探讨,9个样本得到337447条有效序列,经聚类后共得到708个OTU.白头鹤在不同越冬阶段其肠道菌群组成不同,越冬前期拟杆菌门含量较高,厚壁菌门含量较中后期低;越冬中期放线菌门含量较高;越冬后期变形菌门含量较高.在属分类水平,越冬前期以普氏菌属为优势菌;越冬后期以梭菌属为优势菌,不同越冬阶段下的食物变化可能作为影响白头鹤肠道微生物菌群结构的一个重要因素,后期还需要进一步研究其对白头鹤肠道微生物菌群组成的影响机制.

| [1] |

Björkstén B. The gut microbiota: A complex ecosystem. Clinical & Experimental Allergy Journal of the British Society for Allergy & Clinical Immunology, 2006, 36: 1215-1217. |

| [2] |

Ezenwa VO, Gerardo NM, Inouye DW et al. Animal behavior and the microbiome. Science, 2012, 338: 198-199. DOI:10.1126/science.1227412 |

| [3] |

Cani PD, Delzenne NM. The role of the gut microbiota in energy metabolism and metabolic disease. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 2009, 15(13): 1546-1558. DOI:10.2174/138161209788168164 |

| [4] |

Young VB. The intestinal microbiota in health and disease. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology, 2012, 28(1): 63-69. DOI:10.1097/MOG.0b013e32834d61e9 |

| [5] |

Bentley R, Meganathan R. Biosynthesis of vitamin K (menaquinone) in bacteria. Microbiological Reviews, 1982, 46(3): 241-280. |

| [6] |

Mazmanian SK, Hua LC, Tzianabos AO et al. An immunomodulatory molecule of symbiotic bacteria directs maturation of the host immune system. Cell, 2005, 122(1): 107-118. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.007 |

| [7] |

Spor A, Koren O, Ley R. Unravelling the effects of the environment and host genotype on the gut microbiome. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2011, 9(4): 279-290. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro2540 |

| [8] |

Semova I, Carten J, Stombaugh J et al. Microbiota regulate intestinal absorption and metabolism of fatty acids in the zebra fish. Cell Host & Microbe, 2012, 12(3): 277-288. |

| [9] |

Ley RE, Knight R, Gordon JI et al. Evolution of mammals and their gut microbes. Science, 2008, 320(5883): 1647-1651. DOI:10.1126/science.1155725 |

| [10] |

Claesson MJ, Jeffery IB, Conde S et al. Gut microbiota composition correlates with diet and health in the elderly. Nature, 2012, 488(7410): 178-184. |

| [11] |

Zhang Jiachao. Mongolians core gut microbiota and its correlation with dietary changes[Dissertation]. Huhhot: Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, 2014. [张家超. 蒙古族肠道核心菌群及其与饮食关联性研究[学位论文]. 呼和浩特: 内蒙古农业大学, 2014. http://d.g.wanfangdata.com.cn/Conference_8674572.aspx ]

|

| [12] |

Carlotta DF, Duccio C, Monica DP et al. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2011, 43(33): 445-446. |

| [13] |

Zhu LF, Wu Q, Dai JY et al. Evidence of cellulose metabolism by the giant panda gut microbiome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2011, 108(43): 17714-17719. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1017956108 |

| [14] |

Bird Life International. Grus monacha. In: IUCN 2014. The IUCN red list of threatened species. Version 2014.3. Http://www.iucnredlist.org.

|

| [15] |

Yang L, Zhou LZ, Song YW. The effects of food abundance and disturbance on foraging flock patterns of the wintering Hooded Crane (Grus monacha). Avian Research, 2015, 6: 15. DOI:10.1186/s40657-015-0024-z |

| [16] |

Pan Yunfen, Xu Qing, Cheng Yuanqi et al. Herbaceous seed elora of wetlands in Shengjin Lake Nature Reserve of Anhui Province. Wetland Science, 2008, 6: 304-308. [潘云芬, 徐庆, 程元启等. 安徽升金湖自然保护区湿地草本种子植物区系研究. 湿地科学, 2008, 6: 304-308.] |

| [17] |

Liu Zhengyuan, Xu Wenbin, Wang Qishan et al. Environmental carrying capacity for over-wintering Hooded Cranes in Shengjin Lake. Resources and Environment in the Yangtze Basin, 2001, 10(5): 454-459. [刘政源, 徐文斌, 王岐山等. 白头鹤在升金湖上湖越冬期环境容纳量的研究. 长江流域资源与环境, 2001, 10(5): 454-459.] |

| [18] |

Zheng M, Zhou LZ, Zhao NN et al. Effects of variation in food resources on foraging habitat use by wintering Hooded Cranes (Grus monacha). Avian Research, 2015, 6: 11. DOI:10.1186/s40657-015-0020-3 |

| [19] |

Bishop Mary Anne, Li Fengshan. Effects of farming practices in Tibet on wintering Black-necked Crane (Grus nigricollis) diet and food availability. Chinese Biodiversity, 2002, 10(4): 393-398. [Bishop Mary Anne, 李凤山. 农业耕作活动对西藏越冬黑颈鹤食性及食物可获得性的影响. 生物多样性, 2002, 10(4): 393-398.] |

| [20] |

Zhou Lulu. Seasonal shifts of food habit of the Hooded Crane (Grus monacha) wintering in the lakes of Yangtze River Floodplain in Anhui Province[Dissertation]. Hefei: Anhui University, 2013. [周璐璐. 安徽沿江湖泊越冬白头鹤(Grus monacha)食性的季节变化[学位论文]. 合肥: 安徽大学, 2013. http://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/Thesis_Y2321550.aspx ]

|

| [21] |

Zhou B, Zhou L, Chen J et al. Diurnal time-activity budgets of wintering Hooded Cranes (Grus monacha) in Shengjin Lake, China. Waterbirds, 2010, 33(1): 110-115. DOI:10.1675/063.033.0114 |

| [22] |

Dennis KL, Yunwei W, Blatner NR et al. Adenomatous polyps are driven by microbe-instigated focal inflammation and are controlled by il-10-producing T cells. Cancer Research, 2013, 73(19): 5905-5913. DOI:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1511 |

| [23] |

Amato KR, Yeoman CJ, Kent A et al. Habitat degradation impacts black howler monkey (Alouatta pigra) gastrointestinal microbiomes. Isme Journal, 2013, 7(7): 1344-1353. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2013.16 |

| [24] |

Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM et al. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microb, 2007, 73(16): 5261-5267. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00062-07 |

| [25] |

Schloss PD, Dirk G, Westcott SL. Reducing the effects of PCR amplification and sequencing artifacts on 16S rRNA-based studies. PLoS One, 2011, 6(12): e27310. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0027310 |

| [26] |

Susanne M, Katiana S, Christiana H et al. Differences in fecal microbiota in different european study populations in relation to age, gender, and country: A cross-sectional study. Applied & Environmental Microbiology, 2006, 72(2): 1027-1033. |

| [27] |

Lowe BA, Marsh TL, Isaacs-Cosgrove N et al. Defining the "core microbiome" of the microbial communities in the tonsils of healthy pigs. Bmc Microbiology, 2012, 12(1): 20. DOI:10.1186/1471-2180-12-20 |

| [28] |

Donnell MMO, Harris HMB, Jeffery IB et al. The core faecal bacterial microbiome of Irish thoroughbred racehorses. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 2013, 57(6): 492-501. DOI:10.1111/lam.2013.57.issue-6 |

| [29] |

Lu J, Domingo JS. Turkey fecal microbial community structure and functional gene diversity revealed by 16S rRNA gene and metagenomic sequences. Journal of Microbiology, 2008, 46(5): 469-477. DOI:10.1007/s12275-008-0117-z |

| [30] |

Godoy-Vitorino F, Goldfarb KC, Karaoz U et al. Comparative analyses of foregut and hindgut bacterial communities in hoatzins and cows. Isme Journal, 2012, 6(3): 531-541. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2011.131 |

| [31] |

Turnbaugh PJ, Micah H, Tanya Y et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature, 2009, 457(7228): 480-484. DOI:10.1038/nature07540 |

| [32] |

Ley RE, Fredrik B, Peter T et al. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2005, 102(31): 11070-11075. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0504978102 |

| [33] |

Salyers AA. Bacteroides of the human lower intestinal tract. Annual Review of Microbiology, 1984, 38(1): 293-313. DOI:10.1146/annurev.mi.38.100184.001453 |

| [34] |

Meimandipour A, Hair-Bejo M, Shuhaimi M et al. Gastrointestinal tract morphological alteration by unpleasant physical treatment and modulating role of lactobacillus in broilers. British Poultry Science, 2010, 51(1): 52-59. DOI:10.1080/00071660903394455 |

| [35] |

Maslowski KM, Vieira AT, Aylwin N et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor gpr43. Nature, 2009, 461(7268): 1282-1286. DOI:10.1038/nature08530 |

| [36] |

Matsuki T, Watanabe K, Fujimoto J et al. Development of 16S rRNA-gene-targeted group-specific primers for the detection and identification of predominant bacteria in human feces. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2002, 68(11): 5445-5451. DOI:10.1128/AEM.68.11.5445-5451.2002 |

| [37] |

Matsumoto K, Takada T, Shimizu K et al. Effects of a probiotic fermented milk beverage containing lactobacillus casei strain shirota on defecation frequency, intestinal microbiota, and the intestinal environment of healthy individuals with soft stools(brewing and food technology). Journal of Bioscience & Bioengineering, 2010, 110(5): 547-552. |

| [38] |

Mcnulty NP, Tanya Y, Ansel H et al. The impact of a consortium of fermented milk strains on the gut microbiome of gnotobiotic mice and monozygotic twins. Science Translational Medicine, 2011, 3(3): 106r. |

| [39] |

Zhang DM, Zhou LZ, Song YW. Effect of water level fluctuations on temporal-spatial patterns of foraging activities by the wintering Hooded Crane (Grus monacha). Avian Research, 2015, 6: 16. DOI:10.1186/s40657-015-0026-x |

2017, Vol. 29

2017, Vol. 29