泛滥平原生态系统是由河流与其通江湖泊在江湖过渡带的作用下而形成的复杂的河湖复合生态系统网,维持有极高的生物多样性和生产力[1].水位的洪枯变化被认为是维持泛滥平原湖泊鱼类物种组成和分布的主要驱动力[1-4].泛滥平原生态系统的鱼类在长期进化过程中形成了与水位季节性的洪枯变化相适应的生活史周期和节律[5-8].在水温适宜的洪汛初期,长江干流中大量河流性鱼类的产卵由于受到洪水径流的刺激,鱼类资源量急速增长[2, 9-10].随着洪水期的到来,大量仔鱼发育成稚鱼,并随河流洪泛通过江湖过渡带进入泛滥平原湖泊育肥[11-12].进一步随着水位退却和枯水期的到来,在生境滤过作用下大量河流性、江湖洄游性鱼类通过江湖过渡带重返江河[13].因此,江湖过渡带是见证泛滥平原生态系统鱼类交流和多样性变动的关键区域,泛滥平原生态系统的鱼类主要随水位的洪枯变化在江湖连通的支持下通过江湖过渡带进行交流[3, 14].尽管如此,针对江湖过渡带鱼类群落随水位洪枯变化的研究仍然十分匮乏.

在水位洪枯变化的驱动下,泛滥平原湖泊鱼类通过江湖过渡带在河流和湖泊生态系统中进行交流和迁徙,系统解析江湖过渡带鱼类群落的时空动态可以有效评估和验证江湖连通条件下洪泛周期对泛滥平原湖泊鱼类多样性维持的重要意义,为泛滥平原生态系统的鱼类保护提供理论依据.惯常的鱼类群落研究,大多基于鱼类物种数量和丰度计算物种多样性指数进行评估[15].然而,这些指标只在分类特性上提供了生物多样性判断,主要体现生物资源的丰富性[16-17].物种多样性假定不同物种在生态系统中扮演了相同的角色,在研究中常常因为过于简单且敏感性差而饱受争议[18-19].然而,不同物种在生理、生态、形态特征等方面都存在着巨大差异[20-21],生态系统功能不仅依赖于物种的数目,而且依赖于物种所具有的功能特征[20, 22].功能多样性被定义为一个群落中物种功能性状特征的数值、范围、分布和相对丰度情况[23-25].基于功能性状的功能多样性可以将群落中物种的功能性状与生态系统服务和功能有效联系起来[26-28].系统度量洪枯水位变动下江湖过渡带鱼类群落有待综合考虑鱼类的物种和功能多样性.

长江中下游泛滥平原是我国淡水湖泊分布最集中的地区,历史上数百个淡水湖泊与长江干流保持自然连通形成复杂的江湖复合生态系统,维持有极高的生物多样性[29].然而,由于近几十年来人类活动的干扰,很多通江湖泊的自然水文节律受到了不同程度的影响[30].张晓可等[31]基于通江湖泊的通江状况和水位波动节律将长江流域泛滥平原湖泊划分为3种类型,即水库型、间歇型和近自然型,间歇型湖泊和近自然型湖泊水位波动节律与长江干流类似,近自然型湖泊较间歇型湖泊有更大的水位波动变幅,而水库型湖泊水位变幅不大.本研究选取的菜子湖隶属于近自然型湖泊[31],1959年枞阳闸的建立虽在一定程度上影响了菜子湖自然水位波动节律,但该闸长时间的开启状况使得菜子湖仍通过长河与长江干流保持一定程度的自然连通,水位变化显著,平均水位落差达8.5 m[32].此外,菜子湖鱼类的多样性较高,且物种组成近50年保持基本稳定[33],其物种丰度(68种)高于临近面积更大的巢湖(42种)[34-35].随长江洪泛的消长,菜子湖鱼类通过菜子湖湖口以及长河与长江干流进行交流.本研究以菜子湖为例,通过选择菜子湖与长江连通的江湖过渡带进行鱼类群落的系统调查,厘清水位的洪枯变化对鱼类群落物种和功能多样性的影响.在大量泛滥平原湖泊受江湖阻隔和不合理水位调控干扰的背景下,本研究在阐明水位洪枯变化条件下江湖过渡带鱼类物种和功能多样性的时空动态特征的同时,进一步探讨水位的洪泛节律和江湖连通的重要意义,为泛滥平原生态系统鱼类资源保护提供理论基础.

1 材料与方法 1.1 研究区域概况及鱼类调查采集本研究选取的菜子湖江湖过渡带(30°41′~30°48′N,117°05′~117°11′E),包含长河河道(流水生境)和菜子湖入湖口(静水生境)(图 1),过渡带长约16.5 km.根据安徽省水旱情信息网(http://61.191.22.157/Default.aspx)记录的闸门启闭状况数据显示,2017年1月-2018年1月枞阳闸累积开启闸门173天,其中,洪水期(6 -8月)累积开启闸门时间共计65天,水位变幅为10~13 m;枯水期(11 -1月)累积开启闸门时间共计31天,水位变幅为7~10 m;闸门开启持续最长时间为31天.为了有效避免闸门关闭对鱼类群落的不利影响,本研究于2017年选取闸门开启的典型洪枯水位条件进行;洪水期鱼类的采集集中于水位稳定且水位不低于12 m的8月进行,枯水期的鱼类采集集中于水位稳定且水位不高于8 m的12月进行.本研究重点选取静水和流水两个主要生境斑块进行鱼类的定量调查采集.其中,静水生境选取了S1~S10共10个采样点(图 1);流水生境选取了S11~S21共11个采样点(图 1).为了保证采样数据的横向可比性,结合当地渔民惯常的渔业作业方式,鱼类的定量调查采集选取网簖的捕捞方法,网簖由引网、围网、网袋组成[36],每组网簖引网75 m×2 m,围网50 m×10 m,网目3 cm.网簖于前一天傍晚开始放置到第2天的早晨收取,定置时间超过12 h,单位捕捞努力量的渔获量(CPUE)统计为单网渔获量.依据《中国淡水鱼类检索》[37]、《中国动物志·硬骨鱼纲·鲤形目·中卷》[38]和《中国动物志·硬骨鱼纲·鲤形目·下卷》[39]现场进行种类鉴定,并逐条测量体长(标准长度为1 mm)和体重(精确度为0.1 g).对于少数现场未能鉴别的种类,采用10 %的甲醛溶液保存后带回实验室做进一步鉴定和测量.

|

图 1 菜子湖江湖过渡带研究样点分布 Fig.1 Distribution of sampling sites in the ecotone floodplain between Lake Caizi and the Yangtze River |

采用频率和相对多度计算重要值指数分别评估洪水期和枯水期不同生境类型鱼类群落的优势度,重要值指数计算公式为:

| $ {F_i} = 100\% \left( {{S_i}/S} \right) $ | (1) |

| $ {P_i} = 100\% \left( {{N_i}/N} \right) $ | (2) |

| $ IV{I_i} = {10^4} \times {F_i} \cdot {P_i} $ | (3) |

式中,Fi、Pi和IVIi分别代表物种i的频率、相对多度和重要值指数,Si和Ni分别代表物种i的采到次数和累积个体数,S和N分别代表全部采样次数和全部鱼类个体数.

1.2.2 物种多样性指数选取Richness指数、Shannon-Wiener指数、Simpson指数和Pielou指数度量洪枯水位变化下不同生境类型鱼类的物种多样性.

1.2.3 功能多样性指数功能多样性指数用样点×物种和物种×功能性状的矩阵计算,其中功能性状的选择基于既能代表生物在生态系统中的作用,同时又易于测量的标准[28, 40-41]. Villéger等[42]提出功能性状的选取应囊括食物获取能力、移动能力、抵御捕食能力、营养平衡能力和繁殖能力5个维度,基于此,本研究选取了表 1所示的9个功能性状.其中,最大体长、营养级、初次性成熟时间、初次性成熟体长、寿命及生长速率主要参考鱼类数据库Fishbase(http://www.fishbase.org/search.php)[43].体型、生态习性和摄食类群主要参考项目专题报告以及鱼类生态专业知识.

| 表 1 本次研究中所选取的鱼类的功能性状 Tab. 1 List of the functional traits for fish species |

本研究选取功能丰富度指数(Functional Richness, FRic)、功能离散指数(Functional Divergence, FDiv)、功能分散指数(Functional Dispersion, FDis)以及功能均匀度指数(Functional Eveness, FEve)度量洪枯水位变化下不同生境类型鱼类的功能多样性.

功能丰富度指数(FRic)表征一个群落中的物种在性状空间上的填充状况,其计算是利用凸面球拟合的方法(Convex Hull Volume),根据研究的需要可以加入丰度的数据或仅用物种有无的数据,但要求物种数大于功能性状数[44-45].计算公式为:

| $ FRic = \frac{{S{F_{ci}}}}{{{R_c}}} $ | (4) |

式中,FRic为群落i中性状c的功能丰富度指数,SFci为群落中物种所占据的生态位空间,Rc为所有群落中性状c占据的生态位空间.

功能离散指数(FDiv)用来解释物种丰度在功能性状空间的散布情况,度量每个物种与功能上趋异化物种质心的平均距离[45].计算公式为:

| $ {g_k} = \frac{1}{S}\sum\limits_{i = 1}^s {{x_{ik}}} $ | (5) |

| $ d{G_i} = \sqrt {\sum_{k = 1}^T {{{\left( {{x_{ik}} - {g_k}} \right)}^2}} } $ | (6) |

| $ \overline {dG} = \frac{1}{S}\sum\limits_{i = 1}^s d {G_i} $ | (7) |

| $ \Delta d = \sum\limits_{i = 1}^s {{w_i}} \left( {d{G_i} - \overline {dG} } \right) $ | (8) |

| $ \Delta |d| = \sum\limits_{i = 1}^s {{w_i}} \left| {d{G_i} - \overline {dG} } \right| $ | (9) |

| $ FDiv = \frac{{\Delta d + \overline {dG} }}{{\Delta |d| + \overline {dG} }} $ | (10) |

式中,xik为物种i性状k的值,gk为性状k的中心,T为性状数量,dG为物种i与重心的平均距离,d为以多度为权重的离散度,wi为物种i的相对多度.

功能分散指数(FDis)通过计算一个群落中物种构建的性状空间上以物种相对丰富度作为权重算出的物种散布中心,并且计算每个物种与这个中心的平均距离来解释物种在性状空间上的散布情况[46].计算公式为:

| $ c = \frac{{\sum {{w_j}} \cdot {x_{ik}}}}{{\sum {{w_j}} }} $ | (11) |

| $ FDis = \frac{{\sum {{w_j}} \cdot {z_j}}}{{\sum {{w_j}} }} $ | (12) |

式中,c为加权重心,wj为物种j的相对多度,xik为物种i性状k的值,zj为物种j到重心c的加权距离.

功能均匀度指数(FEve)用来解释物种功能性状分布的均匀性和物种丰度分布的均匀性,用最小生成树(MST)的方法计算,要求每个样点的物种数不少于3个[45].计算公式为:

| $ FEve = \frac{{\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{s - 1} {\min } \left( {PE{W_L}, \frac{1}{{S - 1}}} \right) - \frac{1}{{S - 1}}}}{{1 - \frac{1}{{S - 1}}}} $ | (13) |

| $ PE{W_L} = \frac{{E{W_L}}}{{\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{s - 1} E {W_L}}} $ | (14) |

| $ E{W_L} = \frac{{ dist (i, j)}}{{{w_i} + {w_j}}} $ | (15) |

式中,S为物种数,EWL为均匀度权重,dist (i, j)为物种i和j的欧式距离,wi为物种i的相对丰富度;L为分支长,PEWL为分支长权重.

1.2.4 统计分析采用SIMPER分析找出引起水位洪枯变化下菜子湖江湖过渡带不同生境类型鱼类群落结构差异的关键物种,进一步基于重要值指数评估洪水期和枯水期不同生境类型优势鱼类的差异;通过双因素方差分析(Two-way ANOVA)解析水位洪枯变化和不同生境类型对鱼类物种和功能多样性的影响.

物种多样性指数的计算和SIMPER分析利用Primer 6.0软件[47]实现,使用R语言[48]中用“FD”包和“Vegan”包分别进行功能多样性指数的计算以及双因素方差分析,用SigmaPlot 12.5绘图.

2 结果 2.1 鱼类种类组成本研究共采集鱼类4491尾,隶属于6目12科37属52种,其中鲤形目鱼类最多,共37种,占总物种数的71.2 %;鲈形目次之,共8种,占总物种数的15.4 %;鲇形目4种,占总物种数的7.7 %;鲱形目、鲑形目和颌针鱼目各1种,各占总物种数的1.9 %.洪水期和枯水期物种数差异显著,分别采集到鱼类50和42种,其中,太湖新银鱼(Neosalanx tangkahkeii)、马口鱼(Opsariichthys bidens)、中华鳑鲏(Rhodeus sinensis)、高体鳑鲏(Rhodeus ocellatus)、吻鮈(Rhinogobio typus)、大斑花鳅(Cobitis macrostigma)、长须黄颡鱼(Pseudobagrus eupogon)、粗唇拟鲿(Pseudobagrus crassilabris)、大眼鳜(Siniperca kneri)仅在洪水期出现;而银鮈(Squalidus argentatus)和鱵(Hemirhamphus kurumeus)仅在枯水期出现.静水生境和流水生境物种数差异不明显,分别采集到鱼类47和48种(附录Ⅰ).

2.2 生态类型与洪水期相比,枯水期山溪河流性鱼类的物种数、重量、尾数和优势度百分比分别减少了7.3 %、6.3 %、14.4 %和12.0 %;江湖洄游性鱼类的尾数和优势度百分比分别减少了10.2 %和21.1 %;湖泊定居性鱼类的物种数、重量、尾数和优势度百分比分别增加了6.7 %、6.7 %、24.6 %和33.1 % (表 2).

| 表 2 菜子湖江湖过渡带鱼类生态类型 Tab. 2 The ecological types of fish species in the ecotone floodplain between Lake Caizi and the Yangtze River |

与静水生境相比,流水生境山溪河流性鱼类的物种数、重量、尾数和优势度百分比分别增加了5.3 %、14.6 %、18.0 %和22.3 %;江湖洄游性鱼类的物种数、重量、尾数和优势度百分比分别增加了0.7 %、24.9 %、6.2 %和3.4 %;湖泊定居性鱼类的物种数、重量、尾数和优势度百分比分别减少了6 %、39.5 %、24.2 %和25.7 % (表 2).

2.3 群落结构差异贡献种SIMPER分析结果显示,麦穗鱼(Pseudorasbora parva)、蛇鮈(Saurogobio dabryi)、(Hemiculter leucisculus)、鲤(Cyprinus carpio)、鲫(Carassius auratus)、短颌鲚(Coilia brachygnathus)、似鳊(Pseudobrama simoni)、翘嘴鲌(Culter ilishaeformis)、达氏鲌(Culter dabryi)、光唇蛇鮈(Saurogobio gymnocheilus)和无须鱊(Acheilognathus gracilis)是造成枯水期和洪水期及静水生境和流水生境鱼类群落结构差异的主要物种(累积贡献率> 90 %)(表 3).

| 表 3 关键种对枯水期和洪水期以及静水生境和流水生境鱼类群落结构差异的贡献 Tab. 3 Species-specific contributions to the differences of fish assemblages between seasons (dry and wet) and habitat patches(lentic and lotic) |

优势度以重要值大于100为标准,分析结果显示枯水期和静水生境的优势种鱼类相似,重要值较高的优势种鱼类为鲤、鲫、和似鳊;而洪水期和流水生境的优势种鱼类同样相似,重要值较高的优势种鱼类为麦穗鱼(P. parva)、蛇鮈(S. dabryi)、光唇蛇鮈(S. gymnocheilus)和短颌鲚(C. brachygnathus)(表 4).

| 表 4 菜子湖洪水期和枯水期以及静水生境和流水生境鱼类频率、相对多度和重要值指数 Tab. 4 Frequency of occurrence, relative abundance and importance value index for fishes collected in wet and dry seasons as well as lentic and lotic habitat patches of the ecotone floodplain between Lake Caizi and the Yangtze River |

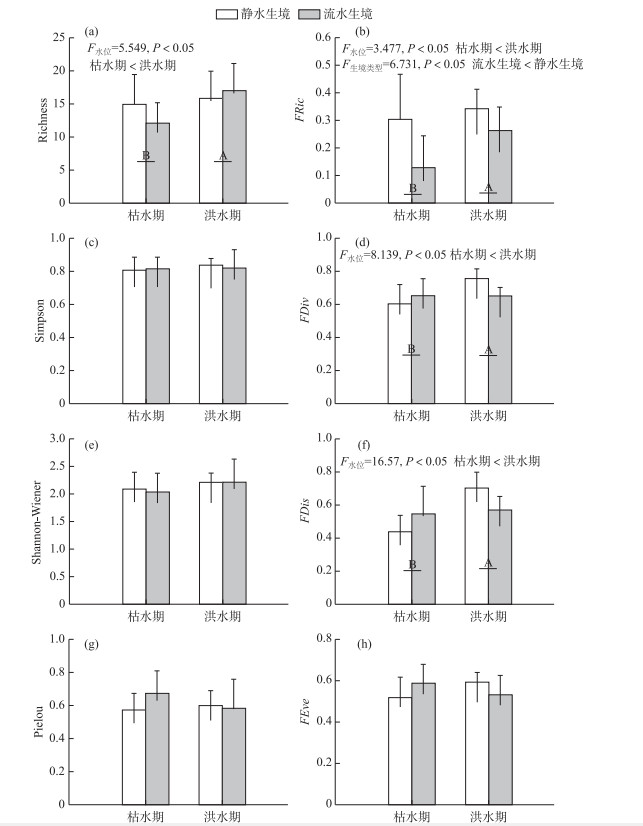

双因素方差分析显示,物种多样性仅Richness指数在洪水期和枯水期之间存在显著差异(图 2).与枯水期相比,洪水期的Richness指数显著更高(F=5.549,P < 0.05).此外,功能多样性的3个指数(FRic、FDiv和FDis)在洪水期和枯水期均有显著差异.与洪水期相比,枯水期的FRic、FDiv和FDis均显著更低(P < 0.05, 图 2b、d、f).同时,静水生境条件下的FRic要显著高于流水生境(F=6.731, P < 0.05).

|

图 2 不同水位季节流水和静水生境斑块内鱼类群落各分类和功能多样性指数(上标不同的字母表示有显著差异(P < 0.05)) Fig.2 Taxonomic and functional diversity indices of fish communities in lentic and lotic habitat patches among wet and dry seasons (Different superscript letters denote significant difference, P < 0.05) |

长江中下游泛滥平原生态系统由众多浅水湖泊通过江湖过渡带与长江干流形成发达的江湖复合生态系统网,鱼类随水位的洪枯变化在江湖连通的支持下通过江湖过渡带进行交流[3, 14].近几十年来, 由于人类活动的干扰(如围网养殖、水位调蓄、大型水利工程建设等),致使江河与湖泊自然连通而形成的江湖复合生态系统受到极大破坏,形成江湖阻隔局面,大多数湖泊鱼类资源由于得不到江河鱼类的补充而面临着急剧下降的问题[10, 49].在本次调查研究中,洪水期所采集到的鱼类物种数(50)比枯水期(42)多出了8种,这主要源自于洪水期流水性鱼类,例如马口鱼、大斑花鳅、长须黄颡鱼和粗唇拟鲿等.随洪泛周期的补充作用,在水温适宜的洪汛初期,长江干流中大量河流性鱼类的产卵由于受到洪水径流的刺激,鱼类资源量急速增长[2, 9-10],随着洪汛中期的到来,大量仔鱼发育成稚鱼,并随洪水径流通过菜子湖江湖过渡带进入菜子湖栖息和觅食[11-12],致使山溪河流性鱼类的数量和百分比大量增加,本研究中洪水期河流性鱼类的物种数、重量、尾数和优势度百分比明显升高.

在季节性洪水脉冲退去的过程中,河湖网络的连接逐渐减少或完全断开[50-51].枯水期,湖泊中的营养物质(如pH、TN、TP等)开始沉降,对某些受环境变化较为敏感的鱼类的生存造成了威胁[13],同时,江水回落所引起的水位下降导致了河湖连通性的减弱,水位急剧降低引起鱼类栖息地空间的萎缩,致使种间作用增强[52-53].本研究中优势度分析结果表明枯水期和静水生境的优势种鱼类相似,重要值较高的优势种鱼类为鲤、鲫和;鲤、鲫和是菜子湖较为常见的一些湖泊定居性鱼类,也是长江中下游泛滥平原湖泊较为常见的耐污种.因此,、鲤和鲫因对环境耐受性较高且种间竞争力更强而成为枯水期和静水生境的优势种鱼类.而在洪水期,河湖之间的连通性增强,使得一些河流性鱼类可以在不同的生境斑块中移动[12, 54].本研究中洪水期和流水生境的优势种鱼类同样相似,重要值较高的优势种鱼类为蛇鮈和光唇蛇鮈,蛇鮈和光唇蛇鮈随着洪水径流经过菜子湖江湖过渡带流入湖中育肥,故而成为洪水期和流水生境的优势种鱼类.

为了进一步分析水位洪枯变化和不同生境类型对菜子湖江湖过渡带鱼类群落的影响,双因素方差分析结果显示功能多样性的3个指数(FRic、FDiv和FDis)均有显著差异(P < 0.05; 图 2b、d、f),而物种多样性指数中,仅物种数在洪、枯水位之间存在显著差异(P < 0.05; 图 2a).物种多样性假定不同的物种具有相同的功能,然而,不同物种在生理、生态、形态特征等方面都存在着巨大差异[20-21].生物多样性的进一步评估需要考虑每个物种在生态系统中或物种对环境条件的响应中的作用[55].相比于物种多样性,基于功能性状的功能多样性全面考虑了物种的生长、繁殖、存活、以及种内种间关系,并且能将群落中物种的功能性状与生态系统服务和功能联系起来[26-28],在本研究中对水位洪、枯变化和不同生境类型的反应表现更为敏感,洪水期的3个功能多样性指数(FRic、FDiv和FDis)显著高于枯水期(P < 0.05; 图 2b、d、f).

FRic指数表征一个群落中的物种在性状空间上的填充状况[56-57].功能丰富度指数由于十分依赖于物种丰富度,对鱼类丰富度的改变非常敏感,通常表现出与物种丰富度指数相同的响应模式[58-60].洪水期,菜子湖与长江之间的连通性增加,大量河流、洄游性鱼类的仔稚鱼随着河流洪泛通过菜子湖江湖过渡带进入菜子湖,极大地补充了湖泊的鱼类资源[12, 54],从而增加了鱼类物种的功能特征值,扩大了鱼类群落功能空间范围,致使洪水期的功能丰富度随着物种丰富度的增加而升高[61-62].此外,静水生境条件下的FRic指数显著高于流水生境(F=6.731, P < 0.05;图 2b).相比于流水生境,静水生境空间更大且能更加稳定地为鱼类提供更丰富的食物资源,致使生境内的鱼类数量更多,因此具有更高的功能丰富度. FDiv指数用来解释物种丰度在功能性状空间的散布情况;FDis指数用来解释物种在性状空间上的散布情况[45, 56].这两种指数已被用来推断种间生态位分化程度和资源互补程度[57-58].枯水期的功能离散度显著低于洪水期(P < 0.05; 图 2d、f),这表明枯水期鱼类群落生态位占据程度更低,竞争更强,对群落中的资源的利用率更低[50-51].营养盐的沉降以及河湖连通性导致的栖息地空间减少,致使种间竞争作用增强,对空间资源利用率更低.

综上所述,物种多样性和功能多样性在比较水位洪枯变化和不同生境类型对鱼类群落的影响时存在差异.在本研究中,物种多样性指数中,仅物种数表现出对水位洪枯变化的敏感性,然而,基于功能性状的功能多样性对水位洪枯变化和不同生境类型均表现出敏感性.结果表明,在水位洪枯之间,菜子湖江湖过渡带的河流洪泛过程为菜子湖的鱼类群落提供了重要的功能补充,这也表明水位的洪枯变化是维持泛滥平原湖泊鱼类种类组成和功能维持的主要驱动力[1-4].因此,在研究水位洪枯变动对鱼类群落的影响时,不能仅仅考虑物种多样性,还应考虑与生态系统功能密切相关的功能多样性.河流周期性洪泛是泛滥平原生态系统对其鱼类群落功能补充的重要途径.最后,尽管人类对水位调节造成严重干扰,本研究表明,维持自然洪水状况和维持水文连通性对于更好地保护泛滥平原生态系统鱼类群落具有重要意义.

4 附录附录Ⅰ见电子版(DOI: 10.18307/2019.0501).

| [1] |

Amoros C, Bornette G. Connectivity and biocomplexity in waterbodies of riverine floodplains. Freshwater Biology, 2002, 47(4): 761-776. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2427.2002.00905.x |

| [2] |

Lytle DA, Poff NLR. Adaptation to natural flow regimes. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2004, 19(2): 94-100. |

| [3] |

Junk WJ. Flood pulsing and the linkages between terrestrial, aquatic, and wetland systems. Internationale Vereinigung für theoretische und angewandte Limnologie:Verhandlungen, 2005, 29(1): 11-38. |

| [4] |

Rood SB, Samuelson GM, Braatne JH et al. Managing river flows to restore floodplain forests. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 2005, 3(4): 193-201. DOI:10.1890/1540-9295(2005)003[0193:MRFTRF]2.0.CO;2 |

| [5] |

Welcomme RL ed. Fisheries ecology of floodplain rivers. New York: Longman publishers, 1979.

|

| [6] |

Winemiller KO. Development of dermal lip protuberances for aquatic surface respiration in South American characid fishes. Copeia, 1989, 2: 382-390. |

| [7] |

Agostinho AA, Gomes LC, Zalewski M. The importance of floodplains for the dynamics of fish communities of the upper river Paraná. International Journal of Ecohydrology & Hydrobiology, 2001, 1(1): 209-217. |

| [8] |

King AJ, Humphries P, Lake PS. Fish recruitment on floodplains:the roles of patterns of flooding and life history characteristics. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 2003, 60(7): 773-786. DOI:10.1139/f03-057 |

| [9] |

Nabout JC, Siqueira T, Bini LM et al. No evidence for environmental and spatial processes in structuring phytoplankton communities. Acta Oecologica, 2009, 35(5): 720-726. DOI:10.1016/j.actao.2009.07.002 |

| [10] |

Ren P, He H, Song Y et al. The spatial pattern of larval fish assemblages in the lower reach of the Yangtze River:potential influences of river-lake connectivity and tidal intrusion. Hydrobiologia, 2016, 766(1): 365-379. DOI:10.1007/s10750-015-2471-2 |

| [11] |

Balcombe SR, Bunn SE, Arthington AH et al. Fish larvae, growth and biomass relationships in an Australian arid zone river:links between floodplains and waterholes. Freshwater Biology, 2007, 52(12): 2385-2398. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2427.2007.01855.x |

| [12] |

Espínola LA, Rabuffetti AP, Abrial E et al. Response of fish assemblage structure to changing flood and flow pulses in a large subtropical river. Marine and Freshwater Research, 2017, 68(2): 319-330. DOI:10.1071/MF15141 |

| [13] |

Nunn AD, Harvey JP, Cowx IG. Benefits to 0+ fishes of connecting man-made waterbodies to the lower River Trent, England. River Research and Applications, 2007, 23(4): 361-376. DOI:10.1002/rra.993 |

| [14] |

Arrington DA, Winemiller KO. Organization and maintenance of fish diversity in shallow waters of tropical floodplain rivers. IN:Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on the Management of Large Rivers for Fisheries. FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific Bangkok, Thailand, 2004, 2: 25-36. |

| [15] |

Pielou EC ed. An introduction to mathematical ecology. New York: Wiley Interscience, 1969.

|

| [16] |

Shannon CE, Weaver W eds. The mathematical theory of communication. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1949.

|

| [17] |

Sun RY, Li B, Zhuge Y et al. General ecology. Beijing: Higher Education Press, 1993. [孙儒泳, 李博, 诸葛阳等. 普通生态学. 北京: 高等教育出版社, 1993.]

|

| [18] |

Von Euler F, Svensson S. Taxonomic distinctness and species richness as measures of functional structure in bird assemblages. Oecologia, 2001, 129(2): 304-311. DOI:10.1007/s004420100732 |

| [19] |

Brosse S, Grenouillet G, Gevrey M et al. Small-scale gold mining erodes fish assemblage structure in small neotropical streams. Biodiversity and Conservation, 2011, 20(5): 1013-1026. DOI:10.1007/s10531-011-0011-6 |

| [20] |

Hooper DU, Vitousek PM. Effects of plant composition and diversity on nutrient cycling. Ecological monographs, 1998, 68(1): 121-149. DOI:10.1890/0012-9615(1998)068[0121:EOPCAD]2.0.CO;2 |

| [21] |

Lepš J, Brown VK, Len TAD et al. Separating the chance effect from other diversity effects in the functioning of plant communities. Oikos, 2001, 92(1): 123-134. DOI:10.1034/j.1600-0706.2001.920115.x |

| [22] |

Diaz S, Hodgson JG, Thompson K et al. The plant traits that drive ecosystems:evidence from three continents. Journal of Vegetation Science, 2004, 15(3): 295-304. DOI:10.1111/j.1654-1103.2004.tb02266.x |

| [23] |

Chapin Iii FS, Zavaleta ES, Eviner VT et al. Consequences of changing biodiversity. Nature, 2000, 405(6783): 234. DOI:10.1038/35012241 |

| [24] |

Loreau M, Hector A. Partitioning selection and complementarity in biodiversity experiments. Nature, 2001, 412(6842): 72. DOI:10.1038/35083573 |

| [25] |

Hooper DU, Chapin FS, Ewel JJ et al. Effects of biodiversity on ecosystem functioning:a consensus of current knowledge. Ecological monographs, 2005, 75(1): 3-35. DOI:10.1890/04-0922 |

| [26] |

Lavorel S, Garnier É. Predicting changes in community composition and ecosystem functioning from plant traits:revisiting the Holy Grail. Functional Ecology, 2002, 16(5): 545-556. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2435.2002.00664.x |

| [27] |

Cornelissen JHC, Lavorel S, Garnier E et al. A handbook of protocols for standardised and easy measurement of plant functional traits worldwide. Australian Journal of Botany, 2003, 51(4): 335-380. DOI:10.1071/BT02124 |

| [28] |

Violle C, Navas ML, Vile D et al. Let the concept of trait be functional! Oikos, 2007, 116(5): 882-892.

|

| [29] |

Zhang X, Liu X, Wang H. Developing water level regulation strategies for macrophytes restoration of a large river-disconnected lake, China. Ecological Engineering, 2014, 68: 25-31. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoleng.2014.03.087 |

| [30] |

Wang SM, Dou HS eds. Lakes of China. Beijing: Science Press, 1998. [王苏民, 窦鸿身. 中国湖泊志. 北京: 科学出版社, 1998.]

|

| [31] |

Zhang X, Qin H, Wang H et al. Effects of water level fluctuations on root architectural and morphological traits of plants in lakeshore areas of three subtropical floodplain lakes in China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2018, 25(34): 34583-34594. DOI:10.1007/s11356-018-3429-5 |

| [32] |

Xu XY, Zhou LZ, Zhu WZ et al. Community structure of macrozoobenthos in Caizi Lake, China. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2011, 31(4): 943-953. [徐小雨, 周立志, 朱文中等. 安徽菜子湖大型底栖动物的群落结构特征. 生态学报, 2011, 31(4): 943-953.] |

| [33] |

Wang CX, Wang ZS, Xu LJ et al. Dynamics of fish community structure in Lake Caizi and its driving factors. Journal of Capital Normal University, 2012, 33(4): 32-37. [王晨旭, 王忠锁, 许隆君等. 菜子湖鱼类区系变动及其驱动力分析. 首都师范大学学报:自然科学版, 2012, 33(4): 32-37.] |

| [34] |

Guo LG, Xie P, Ni LY et al. The status of fishery resources of Lake Chaohu and its response to eutrophication. Acta Hydrobiologica Sinica, 2007, 31(5): 700-705. [过龙根, 谢平, 倪乐意等. 巢湖渔业资源现状及其对水体富营养化的响应研究. 水生生物学报, 2007, 31(5): 700-705. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1000-3207.2007.05.015] |

| [35] |

Wang HK. Remote sensing analysis of water diversion to dilute nutritional condition of Chaohu Lake and inhibition of blue-green algae growth. Water Resources & Power, 2013, 31(4): 54-57. [王化可. 调水至巢湖稀释湖水营养状态及抑制蓝藻生长的遥感分析. 水电能源科学, 2013, 31(4): 54-57.] |

| [36] |

Li W, Li ML, Lian YX et al. The catch structure characteristics of Siniperca chuatsi captured by five fishing gears and its impact on Siniperca chuatsi resources in Xiaosihai Lake. Journal of Fisheries of China, 2015, 39(5): 712-719. [李为, 林明利, 连玉喜等. 肖四海湖五种渔具的鳜渔获结构特征及其对鳜资源的影响. 水产学报, 2015, 39(5): 712-719.] |

| [37] |

朱松泉. 中国淡水鱼类检索. 南京: 江苏科学技术出版社, 1995.

|

| [38] |

Chen YY, Chu XL, Luo YL et al. Fauna sinica:Osteichthyes cypriniformes Ⅱ. Beijing: Science Press, 1998. [陈宜瑜, 褚新洛, 罗云林等. 中国动物志·硬骨鱼纲·鲤形目·中卷. 北京: 科学出版社, 1998.]

|

| [39] |

Yue PQ, Chen YY, Cao WX et al. Fauna sinica:Osteichthyes cypriniformes Ⅱ. Beijing: Science Press, 2000. [乐佩琦, 陈宜瑜, 曹文宣等. 中国动物志·硬骨鱼纲·鲤形目·下卷. 北京: 科学出版社, 2000.]

|

| [40] |

Sibbing FA, Nagelkerke LAJ. Resource partitioning by Lake Tana barbs predicted from fish morphometrics and prey characteristics. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 2000, 10(4): 393-437. DOI:10.1023/A:1012270422092 |

| [41] |

Dumay O, Tari PS, Tomasini JA et al. Functional groups of lagoon fish species in Languedoc Roussillon, southern France. Journal of Fish Biology, 2004, 64(4): 970-983. DOI:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2004.00365.x |

| [42] |

Villéger S, Brosse S, Mouchet M et al. Functional ecology of fish:current approaches and future challenges. Aquatic Sciences, 2017, 79(4): 783-801. DOI:10.1007/s00027-017-0546-z |

| [43] |

Froese R, Pauly D. Fishbase. World wide web electronic publication. http://www/fishbase.org.version(08/2016).

|

| [44] |

Cornwell WK, Schwilk DW, Ackerly DD. A trait-based test for habitat filtering:convex hull volume. Ecology, 2006, 87(6): 1465-1471. DOI:10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[1465:ATTFHF]2.0.CO;2 |

| [45] |

Villéger S, Mason NWH, Mouillot D. New multidimensional functional diversity indices for a multifaceted framework in functional ecology. Ecology, 2008, 89(8): 2290-2301. DOI:10.1890/07-1206.1 |

| [46] |

Laliberté E, Legendre P. A distance-based framework for measuring functional diversity from multiple traits. Ecology, 2010, 91(1): 299-305. DOI:10.1890/08-2244.1 |

| [47] |

Anderson MJ, Gorley RN, Clarke KR eds. PERMANOVA + for PRIMER: Guide to Software and Statistical Methods. Plymouth: Primer-E Limited, 2008.

|

| [48] |

R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: Foundation for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org.2017.

|

| [49] |

Tang S, Zhang T, Lu J et al. Temporal and spatial variation in fish assemblages in Lake Taihu, China. Journal of Freshwater Ecology, 2015, 30(1): 181-196. DOI:10.1080/02705060.2015.1007098 |

| [50] |

Thomaz SM, Bini LM, Bozelli RL. Floods increase similarity among aquatic habitats in river-floodplain systems. Hydrobiologia, 2007, 579(1): 1-13. DOI:10.1007/s10750-006-0285-y |

| [51] |

Melack JM, Novo EMLM, Forsberg BR et al. Floodplain ecosystem processes//Keller M, Bustamante M, Gash J eds. Geophysical monograph series. Washington DC: American Geophysical Union, 2009: 525-541.

|

| [52] |

McConnell R, Lowe-McConnell RH eds. Ecological studies in tropical fish communities. England: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

|

| [53] |

Winemiller KO, Montaña CG, Roelke DL et al. Pulsing hydrology determines top-down control of basal resources in a tropical river-floodplain ecosystem. Ecological Monographs, 2014, 84(4): 621-635. DOI:10.1890/13-1822.1 |

| [54] |

Michels E, Cottenie K, Neys L et al. Zooplankton on the move:first results on the quantification of dispersal of zooplankton in a set of interconnected ponds. Hydrobiologia, 2001, 442(1/2/3): 117-126. |

| [55] |

Villéger S, Miranda JR, Hernández DF et al. Contrasting changes in taxonomic vs. functional diversity of tropical fish communities after habitat degradation. Ecological Applications, 2010, 20(6): 1512-1522. DOI:10.1890/09-1310.1 |

| [56] |

Brandl SJ, Emslie MJ, Ceccarelli DM et al. Habitat degradation increases functional originality in highly diverse coral reef fish assemblages. Ecosphere, 2016, 7(11). DOI: 10.1002/ecs2.1557.

|

| [57] |

Valencia E, Maestre FT, Bagousse-Pinguet L et al. Functional diversity enhances the resistance of ecosystem multi functionality to aridity in Mediterranean dry lands. New Phytologist, 2015, 206(2): 660-671. DOI:10.1111/nph.13268 |

| [58] |

Fischer J, Lindenmayer DB. Landscape modification and habitat fragmentation:a synthesis. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2007, 16(3): 265-280. DOI:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2007.00287.x |

| [59] |

Flynn DFB, Mirotchnick N, Jain M et al. Functional and phylogenetic diversity as predictors of biodiversity-ecosystem-function relationships. Ecology, 2011, 92(8): 1573-1581. DOI:10.1890/10-1245.1 |

| [60] |

Philpott SM, Soong O, Lowenstein JH et al. Functional richness and ecosystem services:bird predation on arthropods in tropical agroecosystems. Ecological Applications, 2009, 19(7): 1858-1867. DOI:10.1890/08-1928.1 |

| [61] |

Mason NWH, Mouillot D, Lee WG et al. Functional richness, functional evenness and functional divergence:the primary components of functional diversity. Oikos, 2005, 111(1): 112-118. DOI:10.1111/j.0030-1299.2005.13886.x |

| [62] |

Bai X, Zhang J. Functional diversity research of forest communities in the Xiaowutai Mountain National Nature Reserve, Hebei. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2018, 38(2): 67-75. DOI:10.1016/j.chnaes.2017.05.003 |

2019, Vol. 31

2019, Vol. 31