拟柱孢藻是热带和亚热带常见的水华藻类之一,具有较强的入侵能力和产毒能力.产CYN的拟柱孢藻于1979年在澳大利亚Palm岛首次被发现,致使148人中毒,引起呕吐、厌食和肝肿大等症状[1].拟柱孢藻毒素是一类环胍类生物碱[2],对小鼠具急性毒性,腹腔注射小鼠的LD50为2.1 mg/kg[2].研究表明,CYN具有肝毒性,神经毒性和细胞毒性,能够抑制谷胱甘肽、细胞色素P450和蛋白质的合成,是一种潜在的致癌物[3-5]. Humpage等[6]以CYN每日最低可见有害作用水平30 μg/kg为基准,建议饮用水中的浓度限值为1 μg/L.目前在澳大利亚[7]、新西兰[8]、东亚、东南亚以及沙特阿拉伯[9-11]等地区都发现了能够产CYN的拟柱孢藻. Mihali等首次在C. raciborskii AWT205藻株中揭示了拟柱孢藻毒素合成酶基因簇的分子特征[12].该基因簇全长43 kb,共包含15个开放阅读框:脒基转移酶基因cyrA,PKS/NRPS基因cyrB、cyrC、cyrD、cyrF和cyrE,尿嘧啶环形成基因cyrG和cyrH,裁剪酶基因cyrI、cyrJ和cyrN,运输基因cyrK,调控基因cyrO,转座酶基因cyrL和cyrM.而基于产毒基因的分子技术具有简单、快速、灵敏等优点,已广泛应用于蓝藻毒素的相关研究,在检测拟柱孢藻的产毒潜能中也逐步得到应用[13].

研究认为拟柱孢藻的成功侵入性主要是由于其能够耐受多种环境条件,如低光照,低温和低营养可利用性[7].此外,Bonilla等也将其生态成功归因于高的表型可塑性[14],这种可塑性实际上来源于多个生态型(即藻株)的存在,而每个生态型都有自己的最佳生理需求[15].即使是分离自同一水体的两株拟柱孢藻同样在形态、藻丝体长度、生长、光照以及温度和营养盐等方面存在差异[16].拟柱孢藻的各个株系并不都产毒,产毒和非产毒株系往往在形态上没有差别,但两者在遗传特征和生理特性上差异较大,此外产毒藻株间也有毒性强弱和毒素种类不同之分[10, 17-18].拟柱孢藻藻株间的差异反映了其高度适应性的策略,推测这也是拟柱孢藻能够快速地理扩张的主要驱动力[7].

蓝藻的分子生物学研究起始于1960s,并被广泛应用于蓝藻分子系统学的研究,随后形成了一门新兴学科藻类分子系统学.运用于蓝藻系统发育研究的分子标记包括16S rDNA、16S~23S rRNA基因间隔序列(ITS)和RNA聚合酶rpoC等[19].由此可见,系统进化树是描述某物种进化历史的重要形式.关于拟柱孢藻的发生和扩散主要有两种假说,第1种假说认为拟柱孢藻的扩散存在非洲和澳大利亚两个扩散中心[20];第2种假说则认为拟柱孢藻对温带地区的入侵不是来自于非洲或澳大利亚,而是每个大陆的温暖避难区[21],即拟柱孢藻是从较温暖的避难地区向美洲和欧洲扩散[22].但最近有研究对上述两个假说均提出质疑,Cirés等根据cpcBA-IGS和nifH基因共建系统进化树,结果发现西班牙的藻株与美洲的拟柱孢藻藻株聚在一起,明显与欧洲其他藻株分开[23],而以前的研究一直认为西班牙藻株是欧洲—亚洲组的一部分,这表明现有的拟柱孢藻系统地理学和扩散途径的假设还有待进一步验证. Manthos等在对希腊的拟柱孢藻藻株进行了系统进化分析提出南美和非洲两个辐射中心,南美辐射中心随后向南美、突尼斯、希腊或西班牙扩张,非洲辐射中心导致了拟柱孢藻从非洲到澳大利亚,然后再向亚洲和欧洲的扩张[24],它为拟柱孢藻的全球扩散提供了一种新的解释.

我国是世界上水体富营养化最严重的国家之一,拟柱孢藻已在多个省份分布,如广东省、福建省、云南省、湖北省、台湾省、山东省和北京等[10-11, 25-27].尤其在南亚热带地区,拟柱孢藻已逐渐取代微囊藻成为水体的优势种群[28],但关于该地区拟柱孢藻产毒特征的研究几乎空白.本研究以从广东省千灯湖分离的10株拟柱孢藻为材料,观察了它们的基本形态特征,采用基于多个CYN毒素合成酶基因的PCR检测和LC-MS/MS对藻株的产毒能力进行了联合分析,并构建了rpoC1和nifH双基因序列的系统发育树.本研究可初步了解南亚热带地区拟柱孢藻的产毒特征和进化起源,为拟柱孢藻水华的风险评估提供参考.

1 材料和方法 1.1 藻株的分离与形态观察千灯湖(23°2′59″N,113°8′29″E)位于广东省佛山市,总库容为5.6×105 m3,平均水深2 m,属于亚热带海洋性季风气候,夏季高温多雨,冬季温和少雨,为小型景观湖泊.水样于2017年9月—2018年2月期间每月采集一次,藻株的分离方法为使用玻璃毛细管在显微镜下吸取单根藻丝体,在无菌水滴中冲洗5~6次,转移到含有1 mL WC培养基的24孔细胞培养板中.培养温度为25 ± 1℃,光照强度为35 μmol /(m2 ·s),光周期为12 h :12 h. 20 d左右使用OLYMPUS TH4-200倒置显微镜镜检,将分离成功的藻株转移至50 mL锥形瓶中继续扩大培养,共计分离出10株拟柱孢藻,命名为QDH1~QDH10.

为观察10株拟柱孢藻生长和形态差异,在50 mL Pyrex玻璃管中加入35 mL藻液,每藻株设置3个重复, 使用TD-700叶绿素荧光仪测定叶绿素a(Chl.a)浓度,培养至第15天时每个样本取2 mL藻液用鲁哥试剂固定,在10×40倍显微镜(ZEISS AX10)下,记录50根藻丝的长度和宽度以及异形胞的形态、长度和宽度.同时采用针对16S rDNA设计的蓝藻特异性引物对27FW和809R(表 1)进行PCR扩增,PCR产物送往公司测序,获得的序列采用BLAST进行相似性分析.比生长速率μ(d-1)指在某一段时间间隔内藻类的生长速率,计算公式[29]为:

| $ \mu=\left[\ln \left(x_{2}\right)-\ln \left(x_{1}\right)\right] /\left(t_{2}-t_{1}\right) $ | (1) |

| 表 1 用于PCR扩增的16S rDNA、rpoC1、nifH基因和产毒基因的引物信息 Tab. 1 Detailed information of primers used for PCR amplification of 16S rDNA, rpoC1, nifH gene and toxigenic genes |

式中,x1为t1时的生物量,x2为t2时的生物量,此处均为Chl.a浓度,μg/L.而t1、t2分别为拟柱孢藻指数生长期的第1天和第7天.

藻丝体的长宽比和比生长率差异采用多重比较分析(Least-significant difference,LSD).所有统计分析和图形绘制在SPSS 22.0和OriginPro 8.0软件中完成.

1.2 产毒基因的PCR扩增选取拟柱孢藻毒素合成酶基因簇中的cyrA、cyrB、cyrC、cyrJ、pks和ps共6个基因,表 1列举了6个基因的特异性引物序列和来源.拟柱孢藻基因组DNA采用植物基因组DNA提取试剂盒(北京鼎国昌盛生物技术有限责任公司)提取,PCR反应体系总体积为30 μL,包括:2×HieffTM PCR Master Mix 15 μL,引物各0.5 μL,DNA模板3 μL,用无菌水补充体积. PCR反应在UNOII Biometra PCR仪上进行,扩增产物采用1 %琼脂糖凝胶电泳,SYRB染色,BIO-RAD凝胶成像系统检测,将有单一目标条带的PCR产物送往公司测序,获得的序列采用BLAST进行相似性分析.

1.3 CYN的LC-MS/MS分析取2 mL新鲜培养的拟柱孢藻藻液,离心后去上清,将藻细胞浸于纯净水中,冰浴下用超声波破碎仪破碎细胞,离心后收集上清,-20℃保存备用.上清中CYN的分析采用AB SCIEX API 3200TM LC/MS/MS系统,以纯度为95 %的CYN(Enzo life science)作为标准品.采集软件为Analyst 1.6.2,离子源为ESI源,采用多反应监测(MRM)正离子模式,CYN的定量离子对为416.2/194.3和416.2/176.3,deoxy-CYN的离子对为400.2/194.3和400.2/176.3.色谱柱为安捷伦Poroshell 120 EC-C18(4.6 mm×50 mm,2.7 μm),柱温为40℃,进样量为20 μL.液相色谱采用梯度模式洗脱,流速0.6 mL/min,流动相为5 %的乙腈.由于deoxy-CYN没有市售的标准品,它的定量根据CYN的标准曲线来计算.

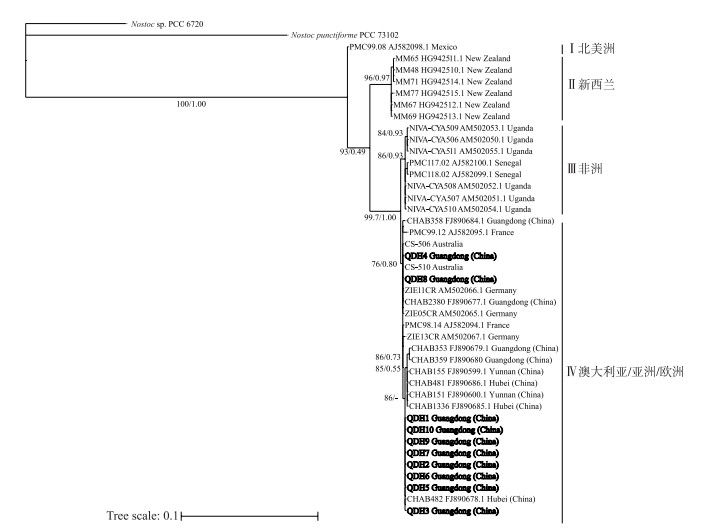

1.4 序列比对与系统发育分析rpoC1基因是蓝藻中编码RNA聚合酶3个最大亚单位的基因,nifH基因是固氮酶基因,是目前拟柱孢藻系统进化研究中最常使用的基因序列.用10株千灯湖拟柱孢藻的nifH和rpoC1序列与从GenBank数据库下载的同源序列构建系统树,两株念珠藻作为外类群,所用藻株的信息和来源见附表 1.采用MEAGE6.0对42株藻的nifH基因序列与rpoC1基因序列进行比对,删除首尾多余序列,将截取出来的序列保存.随后手动将同一株藻的两个基因序列在Notepad++文本软件包中进行串联,串联序列长度为628 bp.以串联序列为材料利用iqtree软件包构建系统发育树,程序中的ModelFinder模块自动计算出最大似然法(ML)的最佳拟合进化模型为GTR+F+G4模型.系统树各分支的置信度由重复抽样法(Bootstrap)1000次重复检测.同时使用MEGA6.0构建最大简约(MP)进化树,以确定进化树的可靠性.进化树的编辑器使用iTOL的在线版本,链接为https://itol.embl.de/upload.cgi.

| 附录Ⅰ 本文所用的拟柱孢藻藻株的来源和登录号 Appendix Ⅰ Geographic location and author of the Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii strains used in this study and the GenBank accession numbers |

将测序所获得的QDH系列藻株的16S rDNA基因序列与GeneBank数据库中的拟柱孢藻16S rDNA进行比对,序列相似性达到了99.6 %,表明在千灯湖分离到的10株丝状藻为拟柱孢藻.数据已上传至NCBI数据库,10株藻的登录号为MK617302~MK617311.

在正常的培养条件下,10株拟柱孢藻的藻丝体形态均为笔直型(图 1),丝体长度范围在41.0~77.7 μm间,宽度范围在2.433~3.125 μm间,对10株藻株藻丝体的长宽比值做LSD分析(表 2),结果QDH9比值最大,为31.491±12.867,除与QDH2和QDH7无差异外与其他藻株差异显著(P < 0.05),QDH4的比值最低,为16.251±6.287.除QDH1藻株外,其他9株千灯湖拟柱孢藻均可产生端生异形胞,其形状如水滴、圆柱或圆锥.在培养过程中,厚壁孢子也可经常观察到,其位置主要有亚端生(如QDH3、QDH4、QDH7和QDH9),双生以及顶端生(QDH5为发育中的厚壁孢子).

|

图 1 千灯湖拟柱孢藻株的形态特征(放大倍数为10×40,a:厚壁孢子,h:异形胞) Fig.1 Morphological characteristics of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii strains isolated from Qiandenghu Lake (The magnification is 10×40, a: akinete, h: heterocyst) |

| 表 2 10株拟柱孢藻的形态特征及比生长速率* Tab. 2 Morphological characteristics and specific growth rate of ten strains of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii |

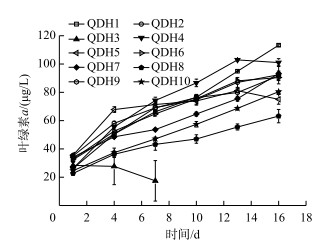

拟柱孢藻QDH3在培养的第3天在玻璃管底部可见大量黄色沉淀,第6天已经死亡.其他9株藻在整个培养周期内生长良好(图 2),在实验结束时,QDH1生物量最高,QDH8最低.对9株藻第1~7天的比生长速率做LSD分析表明(表 2),其中QDH4比生长速率藻株最高,为0.174±0.009 d-1,除与QDH2无差异外与其他藻株均差异极显著(P < 0.001),QDH7的比生长速率最低,为0.075±0.006 d-1,与其他藻株均差异极显著(P < 0.001).

|

图 2 10株千灯湖拟柱孢藻的生长曲线 Fig.2 Growth curves of ten strains of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii from Qiandenghu Lake |

10株拟柱孢藻均检测到cyrB和cyrC基因,而ps和pks基因只在QDH7和QDH9藻株中检出,仅QDH7藻株检测出6个基因(表 3). LC-MS/MS对毒素检测的结果表明,QDH7藻株的毒素检测为阳性,其他9株拟柱孢藻均没有检到拟柱孢藻毒素,QDH7藻株同时检到CYN和deoxy-CYN两种异构体,但异构体CYN浓度极低,deoxy-CYN浓度极高,可达1745.19 ng/mL(表 3).

| 表 3 千灯湖10株拟柱孢藻的产毒基因和拟柱孢藻毒素分析* Tab. 3 Analysis of toxin genes and cylindrospermopsin in ten strains of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii isolated from Qiandenghu Lake |

本研究利用40株(其中10株为本研究分离的藻株)来自不同大陆的拟柱孢藻和2株念珠藻(Nostoc)的双基因(rpoC1和nifH)序列来构建最大似然进化树(ML)与最大简约进化树(MP).在ML进化树上(图 3),来自不同地区的40株拟柱孢藻聚类成4个类群:类群I只包含来自墨西哥的藻株,聚成了北美洲分支;类群Ⅱ包括了新西兰的藻株,聚成了新西兰分支;来自乌干达和塞内加尔的藻株组成类群Ⅲ聚成了非洲分支;类群Ⅳ由来自中国的藻株和欧洲及澳大利亚藻株的组成,聚集成了澳大利亚/亚洲/欧洲分支,在该分支中中国藻株QDH8、QDH4、CHAB2380和CHAB358与来自德国、法国、澳大利亚的藻株聚集成一个亚类群. CHAB系列(除了CHAB482)藻株形成一个分支. CHAB482与QDH系列的其他藻株形成了一个亚类群. MP树的分支情况与ML树一致,也分为4个大类群,分别为:Ⅰ北美洲、Ⅱ新西兰、Ⅲ非洲和Ⅳ澳大利亚/亚洲/欧洲,其中类群IV由两个并系类群组成(图未展示,Bootstrap值添加于ML树中).

|

图 3 基于41株拟柱孢藻和2株念珠藻的rpoC1和nifH基因构建的系统发育树 (Nostoc sp. PCC6720和Nostoc punctiforme PCC73102为外类群,结点上分别为ML和MP的Bootstrap值) Fig.3 Phylogenetic tree inferred from 41 strains of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii using two concatenated genes (rpoC1 and nifH), with Nostoc sp. PCC6720 and Nostoc punctiforme PCC73102 as the outgroup, and the nodes were ML and MP Bootstrap values) |

本研究发现在相同的培养条件下,千灯湖10株拟柱孢藻在生长速度、藻丝体长宽、产毒能力、厚壁孢子和异形胞的形成上存在差异,这与前人的研究基本一致[16-17, 34-35].如Willis等从澳大利亚Wivenhoe湖采集的单个样品中分离到24株拟柱孢藻,发现这些藻株在生长特性、毒素含量和形态等方面均存在差异[17];随后Miotto等从Peri Lagoon湖分离出两株拟柱孢藻,研究显示它们在温度、光照、不同营养盐下的形态、生长速度和毒素产量等方面存在差异[16];Xiao等研究了蓝藻对光照和温度的耐受,发现拟柱孢藻的种内差异甚至大于种间差异,表明拟柱孢藻具有高度的可塑性[35].另外,Yamamoto和Shiah的研究显示同一池塘不同季节分离的拟柱孢藻在比生长速率和厚壁孢子的产生上差异显著[34];Miotto等同样发现Peri Lagoon湖的拟柱孢藻几乎全年都在浮游植物群落中保持优势地位,可能是因为不同生态型对环境的容忍度和偏好导致的[16].本研究分离的10株拟柱孢藻中,QDH1藻株即使在缺氮的条件依然不形成异形胞,但PCR扩增可检测到nifH基因,其序列与NCBI数据库中其他拟柱孢藻nifH基因的相似性达99.4 %,这暗示着该藻株拥有固氮酶基因,但异形胞形成相关的基因存在缺失,已有研究表明异形胞的分化需要大量基因共同参与[36].从千灯湖分离的拟柱孢藻很容易产生厚壁孢子,其他学者的研究中也观察到这种现象[34],一般认为厚壁孢子的产生是拟柱孢藻适应不良环境的结果,这有利于该藻向温带地区入侵[20].

目前共发现了5种拟柱孢藻毒素的同分异构体.拟柱孢藻毒素(CYN)最为常见[2],其次为deoxy-CYN[37],其他3种异构体则极少报道.本研究中分离的千灯湖10藻株仅QDH7可产毒并且以deoxy-CYN异构体为主.这与Jiang等的研究结果类似,他们发现从我国多个水体分离的拟柱孢藻中产毒藻株比例极低,其中有两藻株只产生deoxy-CYN[10],因此推测我国的拟柱孢藻产毒的主要类型为deoxy-CYN,其次为CYN.

拟柱孢藻毒素的合成需要多个基因的分工合作完成,具有完整Cyr基因簇的藻株被认为是区分具产毒潜能与非产毒潜能藻株最明显的特征[12, 18].在本研究中,只有QDH7藻株可完全检出6个基因,其他9株拟柱孢藻只能检出2~5个基因,经LC-MS/MS检测除QDH7外均不产毒,这种产毒基因检测呈阳性但毒素分析为阴性的现象在前人的研究中比较常见[38-39].一些非产毒藻株出现部分产毒基因可能是因为产毒和不产毒蓝藻共存下水平基因转移或插入/删除所致[36, 18, 40-41]. Ballot等在多株非产毒束丝藻中检到cyrA、cyrB和cyrC,认为cyrJ才能较好的指示毒性潜能[38].在我们的研究中,非产毒藻株QDH4和QDH9也有cyrJ基因,但是测序对比分析发现这两株藻的cyrJ基因均缺失了6个碱基(未发表的结果),而Jiang等发现cyrJ存在3种基因类型,可产生CYN的藻株cyrJ基因大多数属于Jtype2a,而我们的QDH4和QDH9是属于Jtype2c[10],这种缺失是否影响到cyrJ的表达尚不清楚, 因此cyrJ基因的指示作用还有待进一步考证.

在探讨世界范围内拟柱孢藻的系统进化和起源时,有研究认为多个遗传标记的共建树比单个遗传标记的区分能力更强大[22, 42];例如Haande等发现pc-IGS、nifH、ITS-L和 rpoC1等单个基因建树不能区分澳大利亚、非洲和欧洲的藻株,但4个遗传标记共建树能够将非洲、澳大利亚、欧洲和美洲的藻株完全区分[22],因此本研究选择两个遗传标记基因nifH和rpoC1共建系统发育树.结果表明澳大利亚、亚洲和欧洲藻株具有更高的同源性,这与前人的研究结果基本一致[24, 43-45].根据Padisák的研究,认为最近拟柱孢藻的入侵是由澳大利亚扩散至亚洲然后再扩散至欧洲,从本文构建的两株双基因系统进化树来看,结果更接近Padisák的假说,推测中国的拟柱孢藻是来自于澳大利亚株系的扩散(图 3).产毒藻株QDH7和其他几株非产毒藻株聚集在一起,表明了它们具有高度的同源性,这表明常规的遗传标记基因难以区分产毒和非产毒株系[18].

4 结论同一水体分离的拟柱孢藻株系在生长特性、形态特征和产毒能力上存在显著差异,即具有多个生态型.从10株拟柱孢藻产毒能力的结果可以看出,千灯湖中的拟柱孢藻以非产毒株占优势,产毒拟柱孢藻以产deoxy-CYN异构体为主.系统进化分析表明,千灯湖的拟柱孢藻与中国其他地区,澳大利亚以及欧洲的藻株同源性较高,千灯湖产毒株与非产毒株聚集在同一分支,基于nifH和rpoC1等常规遗传标记基因构建的系统树不能区分产毒株与非产毒株.

| [1] |

Byth S. Palm Island mystery disease. The Medical Journal of Australia, 1980, 2(1): 40-42. DOI:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1980.tb131814.x |

| [2] |

Ohtani I, Moore RE, Runnegar MTC. Cylindrospermopsin: a potent hepatotoxin from the blue-green alga Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 1992, 114(20): 7941-7942. DOI:10.1002/chin.199303263 |

| [3] |

Humpage AR, Fenech M, Thomas P et al. Micronucleus induction and chromosome loss in transformed human white cells indicate clastogenic and aneugenic action of the cyanobacterial toxin, cylindrospermopsin. Mutation Research, 2000, 472(1/2): 155-161. DOI:10.1016/s1383-5718(00)00144-3 |

| [4] |

Froscio SM, Humpage AR, Burcham PC et al. Cylindrospermopsin-induced protein synthesis inhibition and its dissociation from acute toxicity in mouse hepatocytes. Environmental Toxicology, 2003, 18(4): 243-251. DOI:10.1002/tox.10121 |

| [5] |

Neumann C, Bain P, Shaw G. Studies of the comparative in vitro toxicology of the cyanobacterial metabolite deoxycylindrospermopsin. Journal of Toxicology & Environmental Health, 2007, 70(19): 1679-1686. DOI:10.1080/15287390701434869 |

| [6] |

Humpage A, Falconer I. Oral toxicity of the cyanobacterial toxin cylindrospermopsin in male Swiss albino mice: Determination of no observed adverse effect level for deriving a drinking water guideline value. Environmental Toxicology, 2010, 18(2): 94-103. DOI:10.1002/tox.10104 |

| [7] |

Sinha R, Pearson LA, Davis TW et al. Increased incidence of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii in temperate zones-Is climate change responsible?. Water Research, 2012, 46(5): 1408-1419. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2011.12.019 |

| [8] |

Wood SA, Stirling DJ. The First identification of the cylindrospermopsin-producing cyanobacterium Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 2003, 37(4): 821-828. DOI:10.1080/00288330.2003.9517211 |

| [9] |

Li R, Carmichael WW, Brittain S et al. The first report of the cyanotoxins cylindrospermopsin and deoxycylindrospermopsin from Raphidiopsis curvata (Cyanobacteria). Journal of Phycology, 2001, 37(6): 1121-1126. DOI:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2001.01075.x |

| [10] |

Jiang Y, Xiao P, Yu G et al. Sporadic distribution and distinctive variations of cylindrospermopsin genes in cyanobacterial strains and environmental samples from Chinese freshwater bodies. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2014, 80(17): 5219-5230. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00551-14 |

| [11] |

Lei L, Peng L, Huang X et al. Occurrence and dominance of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii and dissolved cylindrospermopsin in urban reservoirs used for drinking water supply, South China. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 2014, 186(5): 3079-3090. DOI:10.1007/s10661-013-3602-8 |

| [12] |

Mihali TK, Kellmann R, Muenchhoff J et al. Characterization of the gene cluster responsible for cylindrospermopsin biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2008, 74: 716-722. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01988-07 |

| [13] |

Moreira C, Azevedo J, Antunes A et al. Cylindrospermopsin: occurrence, methods of detection and toxicology. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2013, 114(3): 605-620. DOI:10.1111/jam.12048 |

| [14] |

Bonilla S, Aubriot L, Soares MCS et al. What drives the distribution of the bloom-forming cyanobacteria Planktothrix agardhii and Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii?. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2012, 79(3): 594-607. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01242.x |

| [15] |

Chonudomkul D, Yongmanitchai W, Theeragool G et al. Morphology, genetic diversity, temperature tolerance and toxicity of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii (Nostocales, Cyanobacteria) strains from Thailand and Japan. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2004, 48(3): 345-355. DOI:10.1016/j.femsec.2004.02.014 |

| [16] |

Miotto MC, Costa LDF, Brentano DM et al. Ecophysiological characterization and toxin profile of two strains of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii isolated from a subtropical lagoon in Southern Brazil. Hydrobiologia, 2017, 802(1): 97-113. DOI:10.1007/s10750-017-3243-y |

| [17] |

Willis A, Chuang AW, Woodhouse JN et al. Intraspecific variation in growth, morphology and toxin quotas for the cyanobacterium, Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii. Toxicon, 2016, 119: 307-310. DOI:10.1016/j.toxicon.2016.07.005 |

| [18] |

Sinha R, Pearson LA, Davis TW et al. Comparative genomics of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii strains with differential toxicities. BMC Genomics, 2014, 15(1): 83-96. DOI:10.1186/1471-2164-15-83 |

| [19] |

Wilmotte A. Molecular evolution and taxonomy of the cyanobacteria. Molecular Biology of Cyanobacteria, 1994, 1: 1-25. DOI:10.1007/978-94-011-0227-8_1 |

| [20] |

Padisák J. Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii (Woloszynska) Seenayya et Subba Raju, an expanding, highly adaptive cyanobacterium: worldwide distribution and review of its. Arch für Hydrobiol Suppl Monogr, 1997, 107: 563-593. |

| [21] |

Gugger M, Molica R, Le BB et al. Genetic diversity of Cylindrospermopsis strains (Cyanobacteria) isolated from four continents. Appl. Environ. Microbiol, 2005, 71: 1097-1100. DOI:10.1128/AEM.71.2.1097-1100.2005 |

| [22] |

Haande S, Rohrlack T, Ballot A et al. Genetic characterisation of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii (Nostocales, Cyanobacteria) isolates from Africa and Europe. Harmful Algae, 2008, 7: 692-701. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2008.02.010 |

| [23] |

Cirés S, Wörmer L, Ballot A et al. Phylogeography of cylindrospermopsin and paralytic shellfishtoxin-producing Nostocales cyanobacteria from Mediterranean Europe (Spain). Appl Environ Microbiol, 2014, 80: 1359-1370. DOI:10.1128/AEM.03002-13 |

| [24] |

Manthos P, Sevasti-Kiriaki Z, Triantafyllos K et al. A Greek Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii strain: Missing link in tropic invader's phylogeography tale. Harmful Algae, 2018, 80: 96-106. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2018.10.002 |

| [25] |

Wu Z, Shi J, Xiao P et al. Phylogenetic analysis of two cyanobacterial genera Cylindrospermopsis and Raphidiopsis based on multi-gene sequences. Harmful Algae, 2011, 10(5): 419-425. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2010.05.001 |

| [26] |

Yamamoto Y, Shiah FK, Hsu SC. Seasonal variation in the net growth rate of the cyanobacterium Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii in a shallow artificial pond in northern Taiwan. Plankton and Benthos Research, 2013, 8(2): 68-73. DOI:10.3800/pbr.8.68 |

| [27] |

Xie JL, Yu GL, Xu XD et al. The morphological and molecular detection for the presence of toxic Cylindrospermopsis (Nostocales, Cyanobacteria) in Beijing city, China. Journal of Oceanology and Limnology, 2018, 36(2): 1-10. |

| [28] |

Zhao L, Lei LM, Peng L et al. Seasonal dynamic and driving factors of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii in Zhenhai Reservoir, Guangdong Province. J Lake Sci, 2017, 29(1): 193-199. [赵莉, 雷腊梅, 彭亮等. 广东省镇海水库拟柱孢藻(Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii)的季节动态及驱动因子分析. 湖泊科学, 2017, 29(1): 193-199. DOI:10.18307/2017.0121] |

| [29] |

Baker ET, Lavelle JW. The effect of particle size on the light attenuation coefficient of natural suspensions. Journal of Geophysical Research Oceans, 1984, 89(C5). DOI:10.1029/JC089iC05p08197 |

| [30] |

Jungblut AD, Hawes I, Mountfort D et al. Diversity within cyanobacterial mat communities in variable salinity meltwater ponds of McMurdo Ice Shelf, Antarctica. Environmental Microbiology, 2005, 7(4): 519-529. DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00717.x |

| [31] |

Kellmann R, Mills T, Neilan BA. Functional modeling and phylogenetic distribution of putative cylindrospermopsin biosynthesis enzymes. Journal of Molecular Evolution, 2006, 62(3): 267-280. DOI:10.1007/s00239-005-0030-6 |

| [32] |

Schembri MA, Neilan BA, Saint CP. Identification of genes implicated in toxin production in the cyanobacterium Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii. Environmental Toxicology, 2001, 16(5): 413-421. DOI:10.1002/tox.1051 |

| [33] |

Fergusson KM. Multiplex PCR assay for Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii and cylindrospermopsin-producing cyanobacteria. Environmental Toxicology, 2003, 18(2): 120-125. DOI:10.1002/tox.10108 |

| [34] |

Yamamoto Y, Shiah FK. Growth, trichome size and akinete production of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii, (cyanobacteria) under different temperatures: Comparison of two strains isolated from the same pond. Phycological Research, 2014, 62(2): 147-152. DOI:10.1111/pre.12040 |

| [35] |

Xiao M, Willis A, Burford MA. Differences in cyanobacterial strain responses to light and temperature reflect species plasticity. Harmful Algae, 2017, 62: 84-93. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2016.12.008 |

| [36] |

Stucken K, John U, Cembella A et al. The smallest known genomes of multicellular and toxic cyanobacteria: Comparison, minimal gene sets for linked traits and the evolutionary implications. PLoS ONE, 2010, 5(2): e9235. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0009235 |

| [37] |

Norris RL, Eaglesham GK, Pierens G et al. Deoxycylindrospermopsin, an analog of cylindrospermopsin from Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii. Environ Toxicol, 1999, 14: 163-165. DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1522-7278(199902)14:1<163::AID-TOX21>3.0.CO;2-V |

| [38] |

Ballot A, Ramm J, Rundberget T et al. Occurrence of non-cylindrospermopsin-producing Aphanizomenon ovalisporum and Anabaena bergii in Lake Kinneret (Israel). Journal of Plankton Research, 2011, 33: 1736-1746. DOI:10.1093/plankt/fbr071 |

| [39] |

Fathalli A, Jenhani ABR, Moreira C et al. Genetic variability of the invasive cyanobacteria Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii from Bir M'cherga reservoir (Tunisia). Arch Microbiol, 2011, 193: 595-604. DOI:10.1007/s00203-011-0704-y |

| [40] |

Christiansen G, Molitor C, Philmus B et al. Nontoxic strains of cyanobacteria are the result of major gene deletion events induced by a transposable element. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 2008, 25: 1695-1704. DOI:10.1093/molbev/msn120 |

| [41] |

Moustafa A, Loram JE, Hackett JD et al. Origin of saxitoxin biosynthetic genes in cyanobacteria. PLoS ONE, 2009, 4: 57-58. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0005758 |

| [42] |

Moreira C, Fathalli A, Vasconcelos V et al. Phylogeny and biogeography of the invasive cyanobacterium Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii. Arch Microbiol, 2015, 197: 47-52. DOI:10.1007/s00203-014-1052-5 |

| [43] |

Dyble J, Paerl HW, Neilan BA. Genetic characterization of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii (Cyanobacteria) isolates from diverse geographic origins based on nifH and cpcBA-IGS nucleotide sequence analysis. Applied & Environmental Microbiology, 2002, 68(5): 2567-2571. DOI:10.1128/AEM.68.5.2567-2571.2002 |

| [44] |

Neilan BA, Saker ML, Fastner J et al. Phylogeography of the invasive cyanobacterium Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii. Mol Ecol, 2003, 12: 133-140. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01709.x |

| [45] |

Moreira C, Fathalli A, Vasconcelos V et al. Genetic diversity and structure of the invasive toxic cyanobacterium Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii. Current Microbiology, 2011, 62(5): 1590-1595. DOI:10.1007/s00284-011-9900-x |

| [46] |

Wood SA, Pochon X, Luttringer-Plu L et al. Recent invader or indicator of environmental change? A phylogenetic and ecological study of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii in New Zealand. Harmful Algae, 2014, 39: 64-74. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2014.06.013 |

| [47] |

Saker ML ed. Cyanobacterial blooms in tropical north Queensland water bodies. Townsville: Thesis, James Cook University, 2000.

|

| [48] |

Mevarech M, Haselkorn RR. [Part 2: Biological Sciences] || Nucleotide Sequence of a Cyanobacterial nifH Gene Coding for Nitrogenase Reductase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1980, 77(11): 6476-6480. DOI:10.2307/9579 |

2020, Vol. 32

2020, Vol. 32