(2: 格里菲斯大学澳大利亚河流研究所, 澳大利亚昆士兰州 4111)

(3: 瓦格宁根大学环境科学系, 水生态及水质管理组, 荷兰瓦格宁根 6700AA)

(4: 西北农林科技大学资源环境学院, 杨凌 712100)

(2: Australian Rivers Institute, Griffith University, Nathan, QLD 4111, Australia)

(3: Aquatic Ecology & Water Quality Management Group, Department of Environmental Sciences, Wageningen University, P. O. Box 47, 6700 AA, Wageningen, The Netherlands)

(4: College of Natural Resources and Environment, Northwest A&F University, Yangling 712100, P. R. China)

The cyanobacterium Microcystis may form dense blooms throughout water systems around the world, which represents severe ecological and environmental issues[1-3]. The vertical migration capacity of Microcystis is an important trait underlying surface accumulations[4-5]. This migration ability depends on the density of the cyanobacteria-interplay between gas vesicles and carbohydrate ballast-, as well as the colony size and morphology, which are affected by turbulence[6-7]. Therefore, insight is needed in the influence of turbulence on colony size and morphology of Microcystis to understand the effect of turbulence on cyanobacterial blooms and surface accumulations.

The effect of turbulence on the colony size of Microcystis has mainly been studied in the laboratory. Some scholars[8-10] found that small-scale turbulence could increase the colony size of Microcystis in laboratory experiments. However, this was mainly because small-scale turbulence promoted the mixing of carbon dioxide and nutrients in the culture equipment, as well as the colonies, which brought them continuously in higher light that, consequently, improved Microcystis growth. Li et al.[7] reported that artificial high turbulence could change the colony size and morphology of some Microcystis species. Nevertheless, their work indicated that the natural wind-induced turbulence could not disaggregate Microcystis colonies, whereas O'Brien et al.[11] got the opposite result.

Only one study has explored the effect of wind-waves on the colony size of Microcystis in field conditions[12]. These authors found that the mean size of Microcystis colonies in the water column increased from 32.8 to 69.4 μm within 48 h during the passage of Typhoon Soulik, when the average wind speed was 6.63 m/s[12]. This result does not rule out the possibility that wind-waves changed the microenvironment so that the growth of Microcystis was promoted, thereby increasing the colony size. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct high-frequency systematic monitoring in the field to study the relationship between wind-waves or turbulence and the colony size of Microcystis.

The different Microcystis colonies have been interpreted as being different species[13]. There are obvious seasonal successions of M. ichthyoblabe, M. wesenbergii, and M. aeruginosa in most eutrophic lakes[14-16]. Recently, Xiao et al.[13] proposed a conceptual model of the morphological transition of a Microcystis colony, pointing out phenotypic plasticity rather than species replacement to explain various Microcystis morphotypes. Subsequently, Li et al.[7] confirmed in an indoor experiment that turbulence could change the colony morphology of Microcystis. All of these results suggest that Microcystis with different morphologies belong to the same species and that morphology is constantly changing. However, it is important to conduct field research to obtain evidence for the transition of colony morphology. According to the morphology change model proposed by Xiao et al.[13], turbulence could potentially drive M. ichthyoblabe to M. wesenbergii-like colonies and to M. aeruginosa-like colonies. Hence, reduced biomass in M. ichthyoblabe would be accompanied by increased biomass of M. wesenbergii, and likewise, reduced biomass in M. wesenbergii would be accompanied by increased biomass of M. aeruginosa. Thus, the proportion of M. ichthyoblabe should be negatively related to the proportion of M. wesenbergii and the proportion of M. wesenbergii biomass should be negatively related to the proportion of M. aeruginosa. To verify the above hypothesis, it is necessary to conduct high-frequency measurements of the biomass of different morphologies of Microcystis in lakes.

To this end, it is necessary to analyze colony size and morphological changes in Microcystis under different wind-induced turbulence conditions through high-frequency measurements in situ. Hence, the aims of this study were: (1) to clarify the influence of wind-induced turbulence on colony size of Microcystis in the field; (2) to intensively investigate morphology and morphological changes in Microcystis colonies; (3) to provide a systematic data set that can be used in subsequent numerical simulations of Microcystis bloom formation. Therefore, an enclosure was set up in Lake Taihu and the biomass, colony size and morphology of Microcystis at different depths in the enclosure were sampled at 2-h intervals to clarify the effect of turbulence on these parameters and the occurrence of Microcystis blooms.

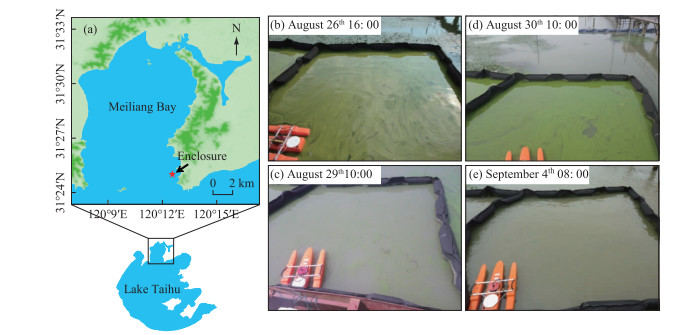

1 Materials and Methods 1.1 Site descriptionOur investigation was conducted in a 4.00 m × 4.00 m enclosure, which was established approximately 150 m away from the eastern shoreline of Meiliang Bay, Lake Taihu (31°25′N, 120°13′E; Fig. 1). The enclosure was made of a flexible geotextile underwater with floating rubber tubing above the surface of the water column, and was open to the atmosphere and to the bottom sediment. The mean water depth in the enclosure during the investigation was approximately 2.00 m and there was no exchange of phytoplankton between the inside and outside of the enclosure.

|

图 1 太湖梅梁湾处围隔的位置及研究期间围隔内水华生消过程 Fig.1 Location of enclosure in Meiliang Bay, Lake Taihu, and appearance and disappearance of bloom event in enclosure during study period |

Sampling was performed every 2 h from 14:00 on August 26 to 12:00 on September 7 in 2012. At each sampling, water samples (50 mL) were collected at varying depths through a slender plastic pipe (diameter 0.004 m) linked to a syringe. Water samples were taken from the surface (0 m) and at 0.10 m, 0.25 m, 0.40 m, 0.80 m, 1.20 m, 1.60 m, and 2.00 m depth. Formalin (2 % (v/v)) was immediately added to the samples before measurements of Microcystis cell density, colony size, and morphology. Meanwhile, equal volumes of water samples were collected at the surface and middle layers of the water column, mixed, and then added into a 500-mL plastic bottle for subsequent nutrient concentration analysis.

1.3 Measurements of environmental factorsAir temperature, light intensity, and wind speed were measured in the field using an electronic thermometer (Mettler SG7, Toledo, OH, USA), a digital lux meter (ZDS-10, Shanghai Xuelian Instruments, China), and a wind recorder (TPJ-30, Zhejiang TOP Instrument Co., Ltd., China), respectively. The wind-driven current in the enclosure was measured using a ship-mounted Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler (ADCP; FlowQuest 2000, San Diego, USA) with its beams downward. The ADCP configuration was set to 0.13 m in bin cells (standard deviation of 0.001 m/s). The 3-dimensional current velocities and directions at different water layers were monitored synchronously every second. However, due to the unreceived reflection of 0.27 m near the ADCP[17-18], the 3-dimensional currents in the 0-0.27 m blind zone were unable to be measured in this study.

The root mean square (RMS) velocity (m/s) was used to define the characteristic speed of the turbulence in each water layer, and was calculated as follows:

| $ \begin{aligned} R M S =\sqrt{\mu_{R M S_{x}}^{2}+\mu_{R M S_{y}}^{2}+\mu_{R M S_{z}}^{2}} \end{aligned} $ | (1) |

| $ \mu_{R M S_{x}} =\sqrt{\frac{\sum \mu_{x}^{2}-\left(\sum \mu_{x}\right)^{2} / n}{n-1}} $ | (2) |

where μRMSx is the fluctuation of the current for Cartesian vector x (which is similarly calculated for the y and z vectors) and n is the number of samples per measurement. The RMS velocities are expressed as averages in different water layers. The turbulent dissipation rate (ε in m2/s3) in each water layer, which describes the turbulence intensity, was calculated from the RMS velocity (m/s)[19] as follows:

| $ \varepsilon=A \frac{R M S^{3}}{h} $ | (3) |

where A is a dimensional constant of order 1[20] and h is the water depth (m) describing the size of the largest vortices.

The turbidity and pH of water samples were measured using a turbidity instrument (WGZ-1, Shanghai Shanke Instrument Factory, Shanghai, China) and a compact pH meter (pH Testr30, Eutech Instruments, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Shanghai, China), respectively. Total nitrogen (TN) and total phosphorus (TP) were measured by spectrophotometry after digestion with alkaline potassium persulfate[21]. Another portion of water samples was filtered through a 0.45-μm pore size membrane and then used to determine total dissolved nitrogen (TDN), total dissolved phosphorus (TDP), nitrate (NO3--N), and ammonium (NH3-N). The analytical methods for TDN and TDP were similar to those for TN and TP, and NO3--N and NH3-N were determined according to the standard methods described by Jin and Tu[22].

1.4 Analysis of cell density, colony size and morphospecies of MicrocystisTo estimate the cell density in each Microcystis sample, a 10-mL centrifuge tube containing 5 mL sample was shaken in a water bath oscillator (100℃, 180 r/min) for approximately 5 min to disperse the colonies completely into single cells[23]. Next, cells were counted at least three times in a blood cell counting chamber under an optical microscope (Olympus CX31; Olympus Corp., Japan) at ×400 magnification. The average value of three results was used as the cell density until the difference between three calculated results was less than 10 %.

Each Microcystis sample was shaken well and then photos were taken using a digital camera (Olympus C-5050) coupled to an optical microscope (Olympus CX31). The photomicrographs were analyzed using UTHSCSA ImageTool v3.00 software[24]. The Microcystis colonies were classified into five morphologies: M. ichthyoblabe, M. aeruginosa, spherical M. wesenbergii, irregular M. wesenbergii, and others, according to the taxonomic methods of Yu et al.[25] and Li et al.[7]. Each individual colony was assumed to be spherical to calculate the biovolume, because it is difficult to accurately measure and calculate the diameter of Microcystis colonies, especially those with irregular morphologies. The diameter (D) of Microcystis colonies was calculated as follows[26]:

| $ D=\sqrt{L \cdot W} $ | (4) |

where, L is the longest axis and W is the shortest axis (aligned perpendicular to the longest axis) of Microcystis colonies. More than 200 colonies per sample were measured to determine the biovolume percentage of various morphospecies for each size group of each morphospecies. The median colony diameter (D50) value was used to estimate the average colony size in all measured samples, which indicated that 50 % of the colonies were smaller than this size [27-28].

1.5 Data analysisIn the current study, the time interval was 24 hours (from noon-12:00 hours- on the first day until noon the next day) and was defined as a complete day. Thus, the sampling period was divided into August 26th, August 27th... September 6th.

The following formula was used to calculate the average cell density of Microcystis (Cave) in the water column:

| $ C_{\mathrm{ave}}=\frac{\sum\limits_{i}^{n} C_{i} \cdot h_{i}}{h} $ | (5) |

where, Ci is the cell density of Microcystis at the depth i, and hi is the height of the water column at depth i (h1=0.010 m; h2=0.165 m; h3=0.150 m; h4=0.275 m; h5=h6=h7=0.400 m; h8=0.200 m), and h is the water depth (2.00 m).

There was a certain deviation in each measurement of cell density of Microcystis. If only two Cave were used to calculate the in situ growth rate, there will be a large systematic error. Hence, a least square linear regression of the natural logarithm of Cave vs. time was performed for each complete day, and the slopes of the regression lines represented the in situ growth rates of Microcystis [29].

The average colony size of Microcystis(D50ave) in the water column was calculated as follows:

| $ D_{50_{\text {ave }} }=\frac{\sum\limits_{i}^{n} D_{50_{i}} \cdot C_{i} \cdot h_{i}}{C_{\text {ave }} \cdot h} $ | (6) |

where, D50i is the average colony size of Microcystis at depth i.

The proportion of each morphospecies (M. ichthyoblabe, M. aeruginosa, spherical M. wesenbergii, irregular M. wesenbergii and others) out of all the Microcystis throughout water column (Pmorphospecies) was calculated as follows:

| $ P_{\text {morphospecies }}=\frac{\sum\limits_{i}^{n} P_{i} \cdot C_{i} \cdot h_{i}}{C_{\text {ave }} \cdot h} $ | (7) |

where, Pi is the proportion of each morphospecies out of all Microcystis at depth i.

Correlation analyses between the in situ growth rate of Microcystis and environmental factors were performed using SPSS 19.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The relationships among the proportions of each morphospecies out of all Microcystis throughout the water column were analyzed via the interval maxima regression (IMR) method[30]. The proportions of two morphospecies were defined as the independent variable and the dependent variable, respectively. First, the independent variables along with the dependent variables were arranged in ascending order. Each independent variable was divided into equal increments, resulting in 18-32 intervals. Next, the maximum dependent variables of every interval were obtained and then fitted linearly with each independent variable. Then, to test the correlation between the fitted data and the original data, a bivariate Pearson's correlation analysis was conducted using SPSS 19.0 software. The relationships between average colony size throughout the water column and wind speed and turbulence dissipation rate were determined by the IMR method. For all analyses, a P value of < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

The minimum-scale of turbulence is determined by the Kolmogorov scale (LK: μm):

| $ \begin{array}{l} L_{\mathrm{K}}=\sqrt{v / \gamma} \end{array} $ | (8) |

| $ \gamma=\sqrt{\varepsilon / v} $ | (9) |

where, υ is kinematic viscosity (0.901×10-6 m2/s at 25℃), γ is shear rate (s-1), ε is turbulent dissipation rate (m2/s3), which is calculated as follows[31]:

| $ \varepsilon=\frac{5.82 \times 10^{-6} w^{3}}{h} $ | (10) |

where, w is wind speed (m/s), and h is water depth (h=2.00 m in this study).

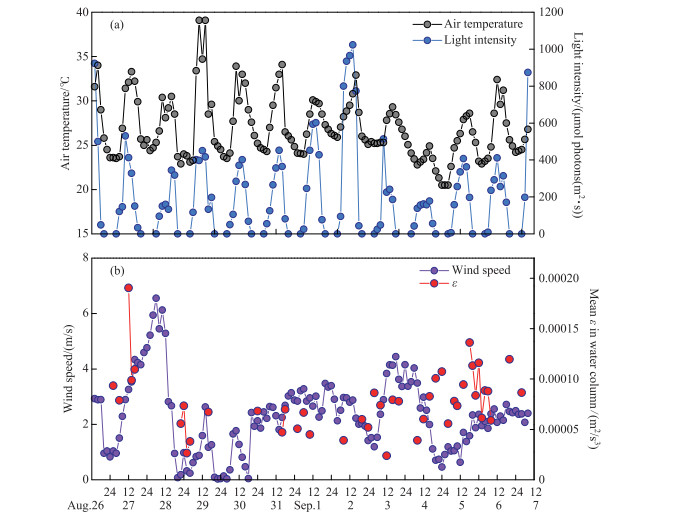

2 Results 2.1 Meteorological factors and nutrient concentrationsThe air temperature showed a distinct diurnal trend of increasing in the morning and decreasing in the afternoon (Fig. 2a). The range of maximum daily air temperature was 24.9-39.1℃, and the average air temperature during the whole study period was 26.9℃. Light intensity showed a similar diurnal trend as air temperature, and the maximum daily light intensity ranged from 178 to 1023 μmol ·photons/(m2 ·s).

|

图 2 研究期间气象因子的昼夜变化 Fig.2 Diel changes in meteorological factors during study period |

The average wind speed was 4.87 m/s from 12:00 on August 27th to 12:00 on August 28th, with a peak wind speed of 6.55 m/s(Fig. 2b). Wind speed above 3.00 m/s could also be observed on September 1st and 4th. The mean turbulence dissipation rate (ε) ranged from 2×10-5 to 19×10-5 m2/s3 and showed the same trend as the wind speed.

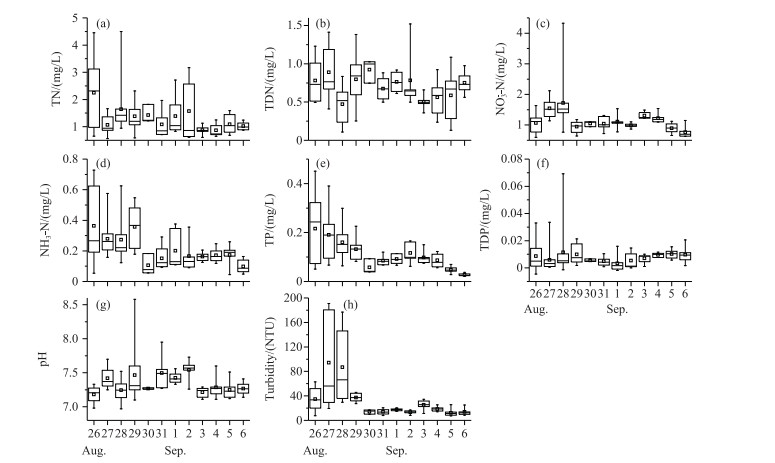

The concentrations of TN, NH3-N, and TP decreased during the survey period (Fig. 3). There were no obvious trends in the changes in TDN and pH, which ranged from 0.51 to 0.86 mg/L and from 7.0 to 8.6, respectively. Turbidity increased significantly on August 27th and 28th, accompanied by an increase in NO3--N and TDP. The average concentrations of NO3--N and TDP declined on August 29th and remained at about 1.015 mg/L and 0.008 mg/L for the following period, respectively (Fig. 3).

|

图 3 研究期间营养盐的变化规律 Fig.3 Temporal variations in nutrient factors during study period |

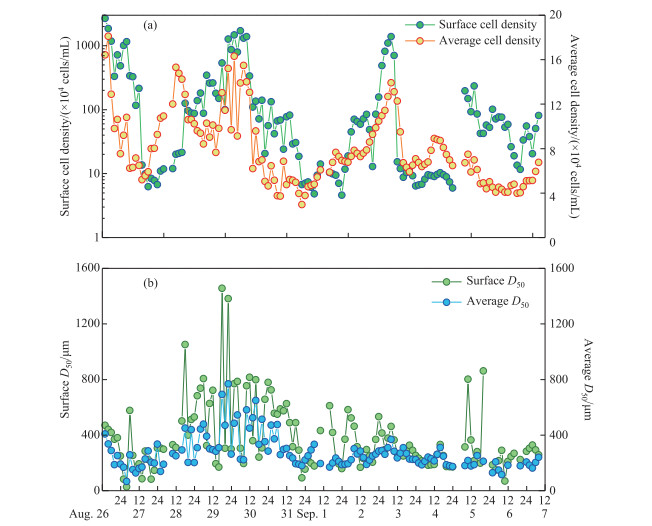

Microcystis was the dominant species, accounting for >99 % of all phytoplankton during the study. The surface cell density of Microcystis fluctuated widely during the study period (Fig. 4a). Microcystis mainly accumulated in the water surface with a high cell density above 1×107 cells/mL on August 26th and 30th and September 3rd. When wind speed was higher than 3.00 m/s on August 28th and September 1st and 4th, the surface cell density decreased to < 2×105 cells/mL. The average cell density in the whole water column varied from 3×104 to 18×104 cells/mL during the study (Fig. 4a).

|

图 4 研究期间微囊藻细胞密度(a)及群体粒径(b)的昼夜变化 Fig.4 Diel changes in cell density (a) and colony size (b) of Microcystis during study period |

The median colony diameter (D50) of Microcystis at the water surface decreased dramatically under strong wind on August 27th (Fig. 4b). After August 28th, the D50 of Microcystis at the surface first increased and then declined. The average D50 of Microcystis through the whole water column was slightly lower than that at the water surface with range of 66.2-768.0 μm. The trend in the variation in D50 in the whole water column also decreased under strong wind on August 27th (Fig. 4b). When wind got down, the D50 in the whole water column increased and then declined.

The proportion of each morphospecies out of all Microcystis at the water surface and in the water column varied over time (Fig. 5). Spherical M. wesenbergii and irregular M. wesenbergii were initially dominant in the surface layer, but the proportions of M. aeruginosa and M. ichthyoblabe increased over time. The trends in the variations of the proportions of Microcystis morphospecies throughout water column can be summarized as follows: the dominant species was M. ichthyoblabe in the early stage of the study, followed by an increase in the proportions of irregular M. wesenbergii and M. aeruginosa, and finally, dominance of M. ichthyoblabe. The proportion of spherical M. wesenbergii in the water column gradually decreased during the study.

|

图 5 研究期间表层及整水柱不同形态微囊藻所占比例的昼夜变化 Fig.5 Diel changes in proportion of each morphospecies out of all Microcystis in surface and water column during study period |

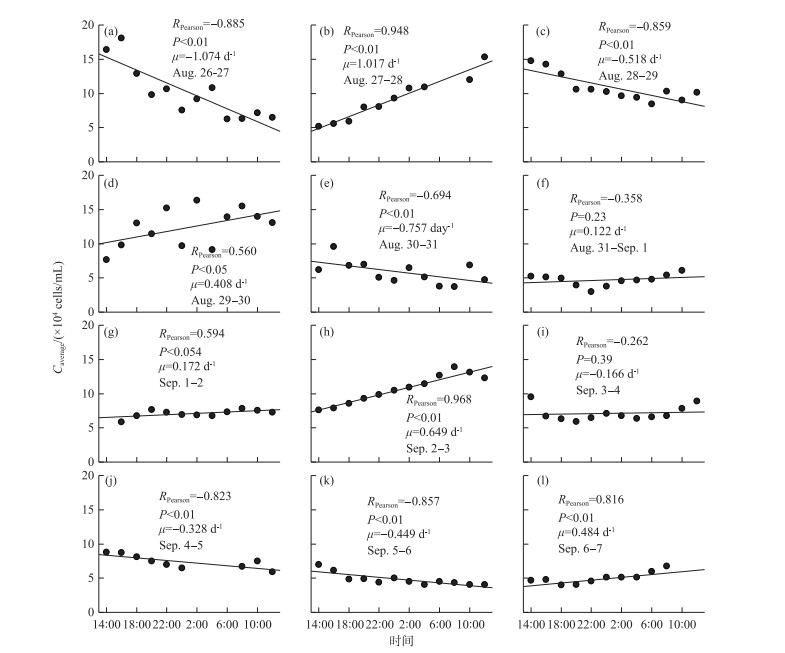

The in situ growth rates of Microcystis obtained by linear fitting are shown in Fig. 6. Except for the growth rate fitting results on August 31st, September 1st, and September 3rd, the other linear fitting results were significant. The in situ growth rate of Microcystis ranged from -1.074 to 1.134 day-1.

|

图 6 研究期间微囊藻原位生长率的变化规律 Fig.6 Temporal variations of in situ growth rates of Microcystis during study period |

Tab. 1 summarizes the results of Pearson's correlation analyses between in situ growth rates of Microcystis and environmental factors based on the daily mean data collected during the field survey. The in situ growth rate of Microcystis was significantly positively correlated with wind speed (P < 0.01) and pH (P < 0.05) and significantly negatively correlated with the surface cell density of Microcystis (P < 0.05). Wind speed was significantly negatively correlated with TDP (P < 0.05). Turbidity was significantly positively correlated with NO3--N (P < 0.01), NH3-N (P < 0.05), and TP (P < 0.01).

| 表 1 Pearson's correlation coefficients of Microcystis in situ growth rates vs. environmental factors and Microcystis cell density during study period Tab. 1 Pearson's correlation coefficients of Microcystis in situ growth rates vs. environmental factors and Microcystis cell density during study period |

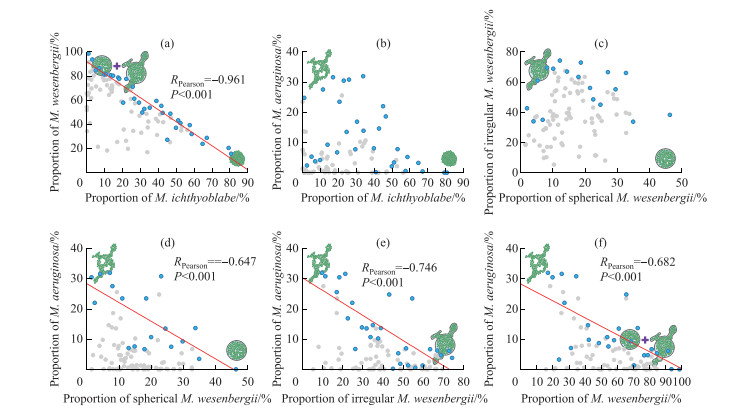

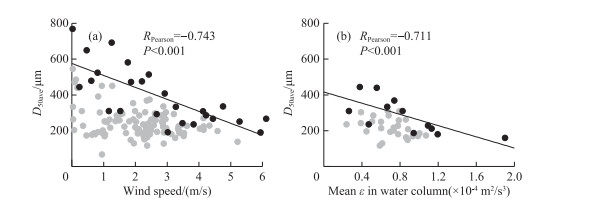

Fig. 7 shows the correlations among the proportions of each morphospecies throughout the water column. The proportion of M. ichthyoblabe out of all Microcystis throughout the water column was negatively (P < 0.001) correlated with that of M. wesenbergii. The proportion of M. aeruginosa was negatively (P < 0.001) correlated with that of spherical M. wesenbergii, irregular M. wesenbergii, and the sum of those two morphospecies. There were significant negative correlations between the average D50 and wind speed and mean ε in the water column (Fig. 8).

|

图 7 不同形态微囊藻所占比例之间的关系(蓝色点代表最大值,灰色点代表除最大值之外其余的值) Fig.7 Relationships among proportion of each morphospecies out of all Microcystis throughout water column (Blue dots indicate maximum values; grey dots depict all data except for maximum values) |

|

图 8 整水柱微囊藻群体平均粒径与风速(a)和平均紊流耗散(b)之间的关系(深灰色点代表最大值,灰色点代表除最大值之外其余的值) Fig.8 Relationships between average colony size of Microcystis throughout water column and (a) wind speeds and (b) mean turbulence dissipation rate(Blue dots indicate maximum values; grey dots depict all data except for maximum values) |

The short-term dynamics of Microcystis biomass in an enclosure ecosystem in a shallow lake was investigated in this study, with the in situ growth rate of Microcystis analyzed by curve-fitting method. The horizontal migration of Microcystis was avoided because of the enclosure ecosystem. The Microcystis biomass was not affected by fish or zooplankton because fish were excluded from the enclosure and the Microcystis colonies in the enclosure ecosystem were too large (D50 > 200 μm (Fig. 4b)) to be predated on by zooplankton[32]. Nevertheless, the cell density of Microcystis in the 1-cm surface water layer was hundreds of times higher than the average cell density in the rest of the water column. Therefore, an accurate assessment of the thickness of Microcystis aggregation on the water surface is an important factor affecting the analytical results, but is almost impossible to achieve. In the current study, surface thicknesses of 0.5 cm, 0.4 cm, 0.3 cm and 0.2 cm were used in calculations. We found that there was no significant difference in the average cell density of Microcystis in the whole water column calculated with the surface thickness of 1 cm (t test, P>0.05, Attached Tab.Ⅰ). Therefore, the in situ growth rate calculated with the surface thickness of 1 cm was deemed reliable.

The majority of the calculated in situ growth rates in the current study were within the range of 0.069 and 0.642 day-1 (Fig. 6), similar to the results measured by the FDC method in other studies[33-34]. The in situ growth rate of Microcystis determined by Cao et al.[35] using specially designed chambers in Lake Taihu was far lower than that determined in our study. This is because they conducted their experiment in spring, when the temperature was much lower than that in the current study (conducted in August). The in situ growth rate of Microcystis measured by the FDC method by Wu and Kong[36] was between 0.2 and 0.3 day-1 in August. However, if the FDC was substituted into formula 1 proposed by Tsujimura[33], the calculated in situ growth rate could reach 0.6 day-1, a value similar to those obtained in this study. Similarly, Wilson et al.[37] reported that the growth rate of individual Microcystis colonies ranged from 0.2 to 0.4 day-1. Li et al.[38] found that the maximum in situ growth rate of Microcystis in Lake Taihu measured by the RNA/TOC method was 0.6 day-1. Although Stolte and Garcés[39] noted that most cyanobacteria have an in situ growth rate of >0.5 day-1, and many show growth rates of >1.0 day-1 in the laboratory, the in situ growth rate of Microcystis in a shallow lake would be < 0.6 day-1 most of the time. However, some of the in situ growth rates calculated in the present study were between -0.3 and -0.5 day-1 (Fig. 6), indicating that there was a considerable decline in the Microcystis even in midsummer. Further studies on the mechanism of Microcystis decline are expected to provide a new ideas for the control of Microcystis blooms.

Our results show that the in situ growth rate of Microcystis was positively related to wind speed, indicating that increasing turbulence promoted Microcystis growth in the field (Tab. 1). It is generally believed that wind-induced turbulence causes the release of nutrient from sediment, thereby stimulating Microcystis growth[40-42]. Turbidity was significantly positively correlated with NO3--N, NH3-N, and TP (Tab. 1). However, the TDP concentration in the current study was negatively correlated with wind speed, suggesting that the release of phosphorus from sediment was limited in the enclosure ecosystem. In addition, we detected no significant relationship between TDP and turbidity (Tab. 1). Tang et al.[43] found that sediment resuspension significantly contributed to the release of particulate phosphorus, but had less of an effect on dissolved phosphorus. This phenomenon was consistent with the nutrient status of phosphorus limitation in Lake Taihu[44-45].

In this current study, the dissolved phosphorus in the water column may have been absorbed by the rapidly growing Microcystis, whose growth was promoted by increasing turbulence. Xie et al.[46] reported a similar result where the TDP concentration in a shallow lake (Lake Donghu, China) decreased due to Microcystis growth. The large number of Microcystis accumulated on the water surface will be under a state of nutrient stress[47-48] and photoinhibition[49-50], which are not conducive to its growth. Sufficient turbulence can cause Microcystis to become evenly distributed in the water column, rather than aggregated at the surface[51-52]. The homodispersion of Microcystis colonies in the water column is conducive to light transmission and nutrient uptake, both of which stimulate Microcystis growth[53-54]. The existence of this pathway was verified by the negative relationship between the in situ growth rate and the surface cell density of Microcystis detected in the current study (Tab. 1). The nitrogen concentration was relatively high in our study, and was not significantly related to the growth rate of Microcystis.

This study showed a significant negative relationship between Microcystis colony size and wind speed during the 12 days of continuous monitoring, indicating that wind-induced turbulence in shallow lakes could break up Microcystis colonies. A similar negative correlation has been demonstrated in the indoor oscillating grids test carried out with Microcystis colonies by O'Brien et al.[11]. Zhang et al.[55] also found the length of Dolichospermum flos-aquae filaments decreased noticeably with the increasing turbulence energy dissipation rates in chemostats with self-designed mixing propellers. The turbulence dissipation rate in the current study ranged from 2×10-5 to 19×10-5 m2/s3, indicating that turbulence at the above intensities could break up Microcystis colonies under natural conditions. According to the relationship between turbulence intensity and wind speed as well as water depth given by MacKenzie and Leggett[31], a turbulence intensity of 2.33×10-5 m2/s3 is equivalent to that produced by an average wind speed of 5.00 m/s in a 30-m depth reservoir. Li et al.[7] showed that the minimum turbulence intensity required to break a Microcystis colony was 0.020 m2/s3 in a laboratory experiment using submerged impellers. The minimum turbulence intensity in the field would be much lower than that in a laboratory because the laboratory experimental time (30 min) was too short to observe disaggregation of Microcystis at lower turbulence intensities. Therefore, the disaggregation of Microcystis colonies by wind-induced turbulence will occur continuously under natural conditions.

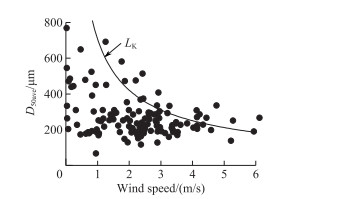

The process of colony formation by cell-adhesion is faster than that by cell-division[56]. Although the extracellular polysaccharides on the surface of Microcystis colonies and cells are negatively charged[57-58], Chen and Lürling[59] showed that Ca2+, an important divalent electrolyte cation in the water, will counteract the electrostatic repulsion to promote the formation of large Microcystis colonies by cell adhesion. Moreover, Qin et al[8] observed that the colony size of Microcystis increased from 32.8 to 69.4 μm under the action of wind-waves, suggesting that strong turbulence could increase the chance of collisions between Microcystis colonies and cells. However, our field results did not show that strong turbulence promoted the adhesion of Microcystis cells or colonies to form larger colonies (Fig. 8). This may be affected by the minimum-scale of turbulence. As shown in Fig. 9, the maximum of D50ave was limited by the LK under different wind speeds. The opposite results between Qin et al.[12] and our study was because the colony size of Microcystis was smaller than LK during their monitoring period. During August 28th to 29th and September 4th to 5th when the wind speed was less than 1.00 m/s, Microcystis colonies aggregated at the water surface (Fig. 4a), resulting in significantly increased D50ave (Fig. 4b). Other studies also found that individual colony size in the surface scums can be up to 2000 μm, but the D50 is usually less than 800 μm[4, 9, 26]. Therefore, low turbulence would promote Microcystis adhesion to form large colonies, but the colony sizes does not exceed the minimum-scale of turbulence.

|

图 9 整水柱微囊藻群体平均粒径与柯尔莫哥洛夫尺度之间的关系 Fig.9 Relationships between average colony size of Microcystis throughout water column and Kolmogorov scale (LK) |

No significant correlation was detected between the proportions of spherical M. wesenbergii and irregular M. wesenbergii (Fig. 7c), although Li et al.[7] have shown that spherical M. wesenbergii can change into irregular M. wesenbergii under the effect of turbulence. The lack of correlation may be caused by M. ichthyoblabe colonies continuously changing into spherical M. wesenbergii colonies, thus interfering with the relationship between spherical M. wesenbergii and irregular M. wesenbergii. However, both the proportions of spherical M. wesenbergii and irregular M. wesenbergii were negatively correlated with that of M. aeruginosa (Fig. 7d, e), indicating that whether M. wesenbergii was deformed or not, their colonies were continuously dissolved and turned into M. aeruginosa. The relationships found in the current study between the various Microcystis colony morphotypes (Fig. 7) support the morphology change model proposed by Xiao et al.[13] that the morphology of Microcystis colonies changes over time. Other researchers[60-62], however, have shown that there are some differences in cell size, mucilage sheath, toxin production, and gene sequences in different morphotypes of Microcystis colonies. In the future studies, it is necessary to measure the above characterization in the dynamic change of Microcystis morphotypes for verifying the hypothesis.

Recent studies have forecasted that global climate change will reduce average wind speeds on land[63-65], resulting in lower turbulence intensity in lakes. The results of this study imply that the colony size of Microcystis in lakes will increase with lower wind speeds, and the probability of surface accumulation will increase. Another prediction from global climate change is an increase in extreme weather events, such as tropical typhoons with high rainfall and winds, which may not only transport nutrients into lakes, but will also stir up sediments[66-68]. In our study, no relation between water column nutrient concentrations and wind speed was found, but at higher winds, such as during typhoons, dissolved inorganic nutrients at the sediment-water interface increased with wind[66]. Consequently, cyanobacterial biomass increased in the next month after tropical cyclones passed[66]. Hence, the availability of nutrients and a more favorable volume-to-surface ratio of smaller colonies due to colony breakage under high winds will promote biomass build-up, while during subsequent stable weather conditions likely larger sized Microcystis colonies will accumulate at the water surface.

The aggregation of Microcystis at the water surface is not conducive to light penetration. Thus, other phytoplankton may receive even less light[13, 65]. Janatian et al.[69] indicated that a decrease in wind speed will shift phytoplankton groups from r-selected coccal and colonial green algae and cyanobacteria to K-selected shade-adapted thin filamentous cyanobacteria in the large and shallow Lake V rtsj rv. Therefore, decreasing wind speed will likely reduce phytoplankton biodiversity in eutrophic lakes, and buoyant cyanobacteria such as Microcystis will become more dominant.

4 ConclusionsStrong turbulence in field conditions promoted Microcystis growth due to homodispersion of Microcystis colonies and release of nutrient from sediment. Microcystis colonies can be disaggregated by strong wind-induced turbulence in the field. The negative relationships between M. ichthyoblabe and M. wesenbergii and between M. wesenbergii and M. aeruginosa in the proportion of morphospecies out of all Microcystis were found in this study, but more evidence is need to support the hypothesis that the morphology of Microcystis colonies changes over time. On the basis of our results, we conclude that a climatically modulated decline in wind speed will promote the surface accumulation of Microcystis due to larger colony formation.

5 AppendixThe Attached Table Ⅰ is seen in the electronic version (DOI: 10.18307/2021.0205).

Supporting InformationThe differences in average cell density of Microcystis in water column calculated by the surface thickness of 1.0 cm, 0.5 cm, 0.4 cm, 0.3 cm and 0.2 cm were analyzed by one-way ANOVA using a Tukey post hoc test. The statistical analysiswere performed using SPSS 19.0.

| Attached Table Ⅰ The differences in average cell density of Microcystis in water column calculated by the surface thickness of 1 cm, 0.5 cm, 0.4 cm, 0.3 cm and 0.2 cm Appendix Attached Table Ⅰ The differences in average cell density of Microcystis in water column calculated by the surface thickness of 1 cm, 0.5 cm, 0.4 cm, 0.3 cm and 0.2 cm |

| [1] |

Harke MJ, Steffen MM, Gobler CJ et al. A review of the global ecology, genomics, and biogeography of the toxic cyanobacterium, Microcystis spp. Harmful Algae, 2016, 54: 4-20. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2015.12.007 |

| [2] |

Kong FX, Gao G. Hypothesis on cyanobacteria bloom-forming mechanism in large shallow eutrophic lakes. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2005, 25(3): 589-595. [孔繁翔, 高光. 大型浅水富营养化湖泊中蓝藻水华形成机理的思考. 生态学报, 2005, 25(3): 589-595. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1000-0933.2005.03.028] |

| [3] |

Yang LY, Yang XY, Ren LM et al. Mechanism and control strategy of cyanobacterial bloom in Lake Taihu. J Lake Sci, 2019, 31(1): 18-27. [杨柳燕, 杨欣妍, 任丽曼等. 太湖蓝藻水华暴发机制与控制对策. 湖泊科学, 2019, 31(1): 18-27. DOI:10.18307/2019.0102] |

| [4] |

Zhu W, Li M, Luo YG et al. Vertical distribution of Microcystis colony size in Lake Taihu: Its role in algal blooms. Journal of Great Lakes Research, 2014, 40(4): 949-955. DOI:10.1016/j.jglr.2014.09.009 |

| [5] |

Wu TF, Qin BQ, Ma JR et al. Movement of cyanobacterial colonies in a large, shallow and eutrophic lake: A review. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2019, 64(36): 3833-3843. [吴挺峰, 秦伯强, 马健荣等. 浅水富营养化湖泊中蓝藻群体运动研究述评. 科学通报, 2019, 64(36): 3833-3843.] |

| [6] |

Li M, Zhu W, Guo LL et al. To increase size or decrease density? Different Microcystis species has different choice to form blooms. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6: 37056. DOI:10.1038/srep37056 |

| [7] |

Li M, Xiao M, Zhang P et al. Morphospecies-dependent disaggregation of colonies of the cyanobacterium Microcystis under high turbulent mixing. Water Research, 2018, 141: 340-348. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2018.05.017 |

| [8] |

Qin BQ, Yang GJ, Ma JR et al. Spatiotemporal changes of cyanobacterial bloom in large shallow eutrophic Lake Taihu, China. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2018, 9: 451. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2018.00451 |

| [9] |

Wu XQ, Noss C, Liu L et al. Effects of small-scale turbulence at the air-water interface on Microcystis surface scum formation. Water Research, 2019, 167: 115091. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2019.115091 |

| [10] |

Yang GJ, Zhong CN, Qin BQ et al. Effects of in-situ simulative mixing on colony size of Micrcocystis in Lake Taihu. J Lake Sci, 2017, 29(2): 363-368. [杨桂军, 钟春妮, 秦伯强等. 野外模拟扰动对太湖微囊藻群体大小的影响. 湖泊科学, 2017, 29(2): 363-368. DOI:10.18307/2017.0212] |

| [11] |

O'Brien KR, Meyer DL, Waite AM et al. Disaggregation of Microcystis aeruginosa colonies under turbulent mixing: laboratory experiments in a grid-stirred tank. Hydrobiologia, 2004, 519(1-3): 143-152. DOI:10.1023/B:HYDR.0000026501.02125.cf |

| [12] |

Qin BQ, Yang GJ, Ma JR et al. Dynamics of variability and mechanism of harmful cyanobacteria bloom in Lake Taihu, China. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2016, 61(7): 759-770. [秦伯强, 杨桂军, 马健荣等. 太湖蓝藻水华"暴发"的动态特征及其机制. 科学通报, 2016, 61(7): 759-770. DOI:10.1360/N972015-00400] |

| [13] |

Xiao M, Li M, Reynolds CS. Colony formation in the cyanobacterium Microcystis. Biological Reviews, 2018, 93(3): 1399-1420. DOI:10.1111/brv.12401 |

| [14] |

Ozawa K, Fujioka H, Muranaka M et al. Spatial distribution and temporal variation of Microcystis species composition and microcystin concentration in Lake Biwa. Environmental Toxicology, 2005, 20(3): 270-276. DOI:10.1002/tox.20117 |

| [15] |

Yamamoto Y, Nakahara H. Seasonal variations in the morphology of bloom-forming cyanobacteria in a eutrophic pond. Limnology, 2009, 10(3): 185-193. DOI:10.1007/s10201-009-0270-z |

| [16] |

Li M, Zhu W, Gao L et al. Seasonal variations of morphospecies composition and colony size of Microcystis in a shallow hypertrophic lake (Lake Taihu, China). Fresenius Environmental Bulletin, 2013, 22: 3474-3483. DOI:10.3318/BIOE.2013.12 |

| [17] |

Vidal J, Casamitjana X, Colomer J et al. The internal wave field in Sau reservoir: Observation and modeling of a third vertical mode. Limnology and Oceanography, 2005, 50(4): 1326-1333. DOI:10.2307/3597412 |

| [18] |

Ponte AL, Gutiérrez De VG, Valle-Levinson A et al. Wind-driven subinertial circulation inside a semienclosed Bay in the Gulf of California. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 2012, 42(6): 940-955. DOI:10.1175/jpo-d-11-0103.1 |

| [19] |

Sanford LP. Turbulent mixing in experimental ecosystem studies. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 1997, 161: 265-293. DOI:10.3354/meps161265 |

| [20] |

Kundu PK, Cohen IM, Dowling DR. Fluid mechanics. Fifth Edition. San Diego: Academic Press, 2012.

|

| [21] |

Ebina J, Tsutsui T, Shirai T. Simultaneous determination of total nitrogen and total phosphorus in water using peroxodisulfate oxidation. Water Research, 1983, 17(12): 1721-1726. DOI:10.1016/0043-1354(83)90192-6 |

| [22] |

Jin XC, Tu QY. Standard of lake eutrophication survey of China. Beijing: China Environmental Science Publishing House, 1990. [金相灿, 屠清瑛. 湖泊富营养化调查规范. 北京: 中国环境科学出版社, 1990.]

|

| [23] |

Joung SH, Kim CJ, Ahn CY et al. Simple method for a cell count of the colonial cyanobacterium, Microcystis sp.. The Journal of Microbiology, 2006, 44(5): 562-565. |

| [24] |

Wilcox D, Dove B, Mcdavid D et al. UTHSCSA image tool for windows version 3.0. The University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, Texas, 2002.

|

| [25] |

Yu GL, Song LR, Li RH. Taxonomic notes on water bloom forming Microcystis species (Cyanophyta) from China—An example from samples of the Dianchi Lake. Acta Phytotaxonomica Sinica, 2007, 45(5): 727-741. [虞功亮, 宋立荣, 李仁辉. 中国淡水微囊藻属常见种类的分类学讨论——以滇池为例. 植物分类学报, 2007, 45(5): 727-741. DOI:10.1360/aps06156] |

| [26] |

Zhu W, Zhou XH, Chen HM et al. High nutrient concentration and temperature alleviated formation of large colonies of Microcystis: Evidence from field investigations and laboratory experiments. Water Research, 2016, 101: 167-175. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2016.05.080 |

| [27] |

Afoakwa EO, Paterson A, Fowler M. Effects of particle size distribution and composition on rheological properties of dark chocolate. European Food Research and Technology, 2008, 226(6): 1259-1268. DOI:10.1007/s00217-007-0652-6 |

| [28] |

Li M, Zhu W, Gao L. Analysis of cell concentration, volume concentration, and colony size of Microcystis via laser particle analyzer. Environmental Management, 2014, 53(5): 947-958. DOI:10.1007/s00267-014-0252-8 |

| [29] |

Yamamoto Y, Shiah FK, Hsu SC. Seasonal variation in the net growth rate of the cyanobacterium Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii in a shallow artificial pond in northern Taiwan. Plankton and Benthos Research, 2013, 8(2): 68-73. DOI:10.3800/pbr.8.68 |

| [30] |

Graham JL, Jones JR, Jones SB et al. Environmental factors influencing microcystin distribution and concentration in the Midwestern United States. Water Research, 2004, 38(20): 4395-4404. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2004.08.004 |

| [31] |

Mackenzie B, Leggett W. Wind-based models for estimating the dissipation rates of turbulent energy in aquatic environments: empirical comparisons. Marine Ecology-Progress Series, 1993, 94: 207-216. DOI:10.3354/meps094207 |

| [32] |

Burns CW. The relationship between body size of filter-feeding Cladocera and the maximum size of particle ingested. Limnology and Oceanography, 1968, 13(4): 675-678. DOI:10.4319/lo.1968.13.4.0675 |

| [33] |

Tsujimura S. Application of the frequency of dividing cells technique to estimate the in situ growth rate of Microcystis (Cyanobacteria). Freshwater Biology, 2003, 48(11): 2009-2024. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2427.2003.01147.x |

| [34] |

Yamamoto Y, Tsukada H. Measurement of in situ specific growth rates of Microcystis (cyanobacteria) from the frequency of dividing cells. Journal of Phycology, 2009, 45(5): 1003-1009. DOI:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2009.00723.x |

| [35] |

Cao HS, Kong FX, Tan X et al. Comparison of recruitment from sediments with pelagic growth of cyanobacteria in Lake Taihu, China. J Lake Sci, 2006, 18(6): 585-589. [曹焕生, 孔繁翔, 谭啸等. 太湖水华蓝藻底泥中复苏和水柱中生长的比较. 湖泊科学, 2006, 18(6): 585-589. DOI:10.18307/2006.0605] |

| [36] |

Wu XD, Kong FX. The determination of in situ growth rates of the bloomed Microcystis in Meiliang Bay, Lake Taihu. China Environmental Science, 2008, 28(6): 552-555. DOI: 1000-6923(2008)28:6<552:SHQJTH>2.0.TX;2-T. [吴晓东, 孔繁翔.水华期间太湖梅梁湾微囊藻原位生长速率的测定.中国环境科学, 2008, 28(6): 552-555. ]

|

| [37] |

Wilson AE, Kaul RB, Sarnelle O. Growth rate consequences of coloniality in a harmful phytoplankter. PLoS One, 2010, 5(1): e8679. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0008679 |

| [38] |

Li M, Zhu W, Dai XX et al. Size-dependent growth of Microcystis colonies in a shallow, hypertrophic lake: use of the RNA-to-total organic carbon ratio. Aquatic Ecology, 2014, 48(2): 207-217. DOI:10.1007/s10452-014-9476-1 |

| [39] |

Stolte W, Garcés E. Ecological aspects of harmful algal in situ population growth rates//Granéli E, Turner JT eds. Ecology of harmful algae. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2006: 139-152.

|

| [40] |

Schelske CL, Carrick HJ, Aldridge FJ. Can wind-induced resuspension of meroplankton affect phytoplankton dynamics?. Journal of the North American Benthological Society, 1995, 14(4): 616-630. DOI:10.2307/1467545 |

| [41] |

Hamilton D, Mitchell S. Wave-induced shear stresses, plant nutrients and chlorophyll in seven shallow lakes. Freshwater Biology, 1997, 38(1): 159-168. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2427.1997.00202.x |

| [42] |

Zhu MY, Paerl HW, Zhu GW et al. The role of tropical cyclones in stimulating cyanobacterial (Microcystis spp.) blooms in hypertrophic Lake Taihu, China. Harmful Algae, 2014, 39: 310-321. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2014.09.003 |

| [43] |

Tang CY, Li YP, He C et al. Dynamic behavior of sediment resuspension and nutrients release in the shallow and wind-exposed Meiliang Bay of Lake Taihu. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 708: 131-135. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135131 |

| [44] |

Xu H, Paerl HW, Qin BQ et al. Nitrogen and phosphorus inputs control phytoplankton growth in eutrophic Lake Taihu, China. Limnology and Oceanography, 2010, 55(1): 420-432. DOI:10.4319/lo.2010.55.1.0420 |

| [45] |

Paerl HW, Xu H, Mccarthy MJ et al. Controlling harmful cyanobacterial blooms in a hyper-eutrophic lake (Lake Taihu, China): The need for a dual nutrient (N & P) management strategy. Water Research, 2011, 45(5): 1973-1983. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2010.09.018 |

| [46] |

Xie LQ, Xie P, Li SX et al. The low TN:TP ratio, a cause or a result of Microcystis blooms?, 2003, 37(9): 2073-2080. Water Research, 2003, 37(9): 2073-2080. DOI:10.1016/S0043-1354(02)00532-8 |

| [47] |

Halstvedt CB, Rohrlack T, Andersen T et al. Seasonal dynamics and depth distribution of Planktothrix spp. in Lake Steinsfjorden (Norway) related to environmental factors. Journal of Plankton Research, 2007, 29(5): 471-482. DOI:10.1093/plankt/fbm036 |

| [48] |

Yan RR, Pang Y, Chen XF et al. Effect of disturbance on growth of Microcystis aeruginosa in different nutrient levels. Environment Science, 2008, 29(10): 2749-2753. [颜润润, 逄勇, 陈晓峰等. 不同风等级扰动对贫富营养下铜绿微囊藻生长的影响. 环境科学, 2008, 29(10): 2749-2753. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0250-3301.2008.10.010] |

| [49] |

Yang DT, Chen WM, Zhang YL et al. Effect of underwater light spectrum on primary production of the Taihu Lake. Journal of Ecology and Rural Environment, 2003, 19(2): 24-28. [杨顶田, 陈伟民, 张运林等. 太湖水体光学特征及其对水中初级生产力的影响. 生态与农村环境学报, 2003, 19(2): 24-28. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-4831.2003.02.006] |

| [50] |

Zhang YL, Qin BQ, Chen WM et al. Experimental study on underwater light intensity and primary productivity caused by variation of total suspended matter. Advances in Water Science, 2004, 15(5): 615-620. [张运林, 秦伯强, 陈伟民等. 悬浮物浓度对水下光照和初级生产力的影响. 水科学进展, 2004, 15(5): 615-620. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1001-6791.2004.05.014] |

| [51] |

Moreno-Ostos E, Cruz-Pizarro L, Basanta A et al. The influence of wind-induced mixing on the vertical distribution of buoyant and sinking phytoplankton species. Aquatic Ecology, 2008, 43(2): 271-284. DOI:10.1007/s10452-008-9167-x |

| [52] |

Wang H, Zhang ZZ, Liang DF et al. Separation of wind's influence on harmful cyanobacterial blooms. Water Research, 2016, 98: 280-292. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2016.04.037 |

| [53] |

Paerl HW, Hall NS, Calandrino ES. Controlling harmful cyanobacterial blooms in a world experiencing anthropogenic and climatic-induced change. Science of the Total Environment, 2011, 409(10): 1739-1745. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.02.001 |

| [54] |

Wallace BB, Hamilton DP. The effect of variations in irradiance on buoyancy regulation in Microcystis aeruginosa. Limnology and Oceanography, 1999, 44(2): 273-281. DOI:10.4319/lo.1999.44.2.0273 |

| [55] |

Zhang SQ, Xiao Y, Li Z et al. Turbulence exerts nutrients uptake and assimilation of bloom-forming Dolichospermum through modulating morphological traits: Field and chemostat culture studies. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 671: 329-338. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.328 |

| [56] |

Xiao M, Willis A, Burford MA et al. Review: a meta-analysis comparing cell-division and cell-adhesion in Microcystis colony formation. Harmful Algae, 2017, 67: 85-91. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2017.06.007 |

| [57] |

Sato M, Amano Y, Machida M et al. Colony formation of highly dispersed Microcystis aeruginosa by controlling extracellular polysaccharides and calcium ion concentrations in aquatic solution. Limnology, 2016, 18(1): 111-119. DOI:10.1007/s10201-016-0494-7 |

| [58] |

Sato M, Omori K, Datta T et al. Influence of extracellular polysaccharides and calcium ion on colony formation of unicellular Microcystis aeruginosa. Environmental Engineering Science, 2017, 34(3): 149-157. DOI:10.1089/ees.2016.0135 |

| [59] |

Chen HM, Lürling M. Calcium promotes formation of large colonies of the cyanobacterium Microcystis by enhancing cell-adhesion. Harmful Algae, 2020, 92: 101768. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2020.101768 |

| [60] |

Song LR, Chen W. Production of microcystins in bloom-forming cyanobacteria and their environmental fates: a review. J Lake Sci, 2009, 21(6): 749-757. [宋立荣, 陈伟. 水华蓝藻产毒的生物学机制及毒素的环境归趋研究进展. 湖泊科学, 2009, 21(6): 749-757. DOI:10.18307/2009.0601] |

| [61] |

Gan NQ, Wei NA, Song LR. Recent progress in research of the biological function of microcystins. J Lake Sci, 2017, 29(1): 1-8. [甘南琴, 魏念, 宋立荣. 微囊藻毒素生物学功能研究进展. 湖泊科学, 2017, 29(1): 1-8. DOI:10.18307/2017.0101] |

| [62] |

Duan ZP, Tan X, Parajuli K et al. Characterization of Microcystis morphotypes: Implications for colony formation and intraspecific variation. Harmful Algae, 2019, 90: 101701. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2019.101701 |

| [63] |

Mcvicar TR, Roderick ML, Donohue RJ et al. Global review and synthesis of trends in observed terrestrial near-surface wind speeds: Implications for evaporation. Journal of Hydrology, 2012, 416: 182-205. DOI:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2011.10.024 |

| [64] |

Wentz FJ, Ricciardulli L, Hilburn K et al. How much more rain will global warming bring?. Science, 2007, 317(5835): 233-235. DOI:10.1126/science.1140746 |

| [65] |

Shi K, Zhang YL, Zhu GW et al. Deteriorating water clarity in shallow waters: Evidence from long term MODIS and in-situ observations. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 2018, 68: 287-297. DOI:10.1016/j.jag.2017.12.015 |

| [66] |

Havens K, Paerl H, Phlips E et al. Extreme weather events and climate variability provide a lens to how shallow lakes may respond to climate change. Water, 2016, 8(6): 1-18. DOI:10.3390/w8060229 |

| [67] |

Luo XC, Hang X, Cao Y et al. Dominant meteorological factors affecting cyanobacterial blooms under eutrophication in Lake Taihu. J Lake Sci, 2019, 31(5): 1248-1258. [罗晓春, 杭鑫, 曹云等. 太湖富营养化条件下影响蓝藻水华的主导气象因子. 湖泊科学, 2019, 31(5): 1248-1258. DOI:10.18307/2019.0512] |

| [68] |

Zhang M, Yang Z, Shi XL. Expansion and drivers of cyanobacterial blooms in Lake Taihu. J Lake Sci, 2019, 31(2): 336-344. [张民, 阳振, 史小丽. 太湖蓝藻水华的扩张与驱动因素. 湖泊科学, 2019, 31(2): 336-344. DOI:10.18307/2019.0203] |

| [69] |

Janatian N, Olli K, Cremona F et al. Atmospheric stilling offsets the benefits from reduced nutrient loading in a large shallow lake. Limnology and Oceanography, 2019, 65(4): 1-9. DOI:10.1002/lno.11342 |

2021, Vol. 33

2021, Vol. 33